The Six Habits of Highly Successful Art Collectors

You don’t have to have millions to invest in art.

—

THINK SMALL

Bill Clarke has never spent more than $2,500 on art. He is living proof that you don’t have to be a millionaire to buy it and that you can be a serious collector with only a limited budget.

Although Clarke moonlights as executive editor of Magenta Magazine, an international art journal, and grew up in a collecting family (his father owns coins from the medieval period), he only started visiting galleries in 2001 after taking a job in the production department of Canadian Art magazine. “I became transfixed by the creativity that routinely crossed my desk,” says Clarke, “and began to think, I want to live with that.”

Two years later, Clarke made his first major purchase, Untitled (cat and rabbit), a drawing by Winnipeg-born Marcel Dzama, after seeing his work exhibited at Toronto’s contemporary art gallery, the Power Plant. (He paid $1,000 for the piece, though it’s now worth more than double that amount.) Clarke was drawn to Dzama’s art because it made him laugh and because it “was by someone my age.” But it helped him come to an important realization. Works on paper are usually far more affordable than paintings, but no less compelling. “Tiny pieces can be very powerful,” says Clarke. “They draw you in because you have to get up close to look.”

Today Clarke is a recognized expert on works on paper. It’s a subject to which he devotes his spare time and income, growing his collection, which he hangs tightly packed in a salon style in his one-bedroom flat. “I could have a closet full of expensive clothes or I could buy art,” he says. “I buy the best that I can with the money I’ve got.”

LOOK AHEAD

There is no way to predict whether an artist will achieve fame, but Joe Friday (that’s his real name, by the way) has a record for spotting stars. Two years after he purchased the four-part photographic series Home-Made Eames (Formers, Jigs and Molds), by Simon Starling—a work also snapped up by the Guggenheim—its maker won the 2005 Turner Prize, the British art-world’s equivalent of an Academy Award. In an equally forward-thinking move, Friday bought pieces by the Vancouver-based, Gershon Iskowitz Prize winner Brian Jungen a decade before he would become the first living Native American artist to have a solo exhibition at Washington’s Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

When Friday began purchasing art in the late 1980s, he says he wasn’t yet a “confident collector,” so he would go to the library at the National Gallery of Canada and compile dossiers on the artists who interested him—including photocopied articles, reviews and career studies. Only when he felt ready to stand up and “make a case” for an artist would he put down his money. Today Friday’s collection is regarded as the most significant private holding of contemporary art in the Ottawa area, but he continues to follow the same rigorous process for making purchases as when he started out, a method he describes as “painful, long, and one that often takes up to six months.”

Something has changed from when Friday began, however: He now feels comfortable buying the work of artists who don’t yet have a track record. It’s the ultimate benefit of 25 years’ worth of research, he explains: “You develop a sense of instinct and intuition.”

JOIN AN ART COMMUNITY

“For some people, it’s about the kill in acquiring a work,” says Shanitha Kachan. “For us, it’s about the journey.” The erudite and congenial Kachan is explaining the genesis of the collection she and her husband, Gerald Sheff (co-founder of the investment firm Gluskin Sheff), started after they married in 1999 and how when it comes to making purchases, “the education comes first and the art comes after.”

The couple’s inaugural purchase was Fantasia for Four Hands by Canadian artist Rodney Graham, a work that quickly became “an anchor” in their newly built, Bruce Kuwabara-designed home. But then, Kachan and Sheff spent two years looking at blank walls before they decided what would come next. “We knew where we wanted to go,” says Kachan, “but we weren’t sure how we were going to get there.” The period coincided with Kachan’s transition from corporate sales (at William Ashley) to the world of art, as she began to volunteer for the Canadian Art Foundation—a move she counts as integral to her becoming a collector. “It takes time to connect with art,” says Kachan, “and we are all so busy.” But, she explains, if you join an art community, either by donating your time or by becoming a gallery member, you will develop a sense of confidence, as you meet people with similar interests and start putting faces to artists’ names.

By 2003, Kachan’s newly minted art knowledge led her and Sheff to their next significant buys: a painting by the British artist Jason Martin and a collaborative piece by Liam Gillick and the Scottish Turner Prize winner Douglas Gordon. When they looked at the works alongside Fantasia for Four Hands, it was a harmonious aha moment. “We saw how the works spoke to one another,” says Kachan, “and decided, let’s keep moving, let’s keep learning.”

LOOK FOR A MENTOR

Twenty-five years ago, when Ann Webb agreed to marry her husband, Marshall, she had a condition. She said to him: “If we are going to buy art together, we need to figure out what we are doing.” In the days following their nuptial vows, the couple began to work toward this goal, inspired by Herb and Dorothy Vogel, a New York postal clerk and a librarian whom they identified as their “collecting mentors.” In their spare time, the Vogels had amassed one of America’s most prominent collections of conceptualist and minimalist art.

It wasn’t that the Webbs needed the Vogels to teach them about art. When the two of them met in 1985 at Toronto’s S.L. Simpson Gallery, Ann was the director’s assistant and Marshall had been buying art for over a decade. But the Vogels’ example offered an education in focus. “When I met Ann I was shopping for art, not collecting it,” Marshall explains. The Webbs admired how the Vogels “bought their contemporaries,” and how they put together a collection so noteworthy that a large portion of it is now owned by Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

Today, each of the Webbs’ art purchases is part of a carefully thought-out plan. Unconstrained by a work’s medium, size, or its maker’s nationality, the couple look for pieces of “poetic conceptualism” by artists “who can teach us about our time.” For as long as they can afford, they buy an artist in “as much depth as possible.” Much like their collecting mentors (the Webbs visited the Vogels in their New York apartment three years ago—Herb died this summer), the Webbs have a discerning vision that has helped define them as one of North America’s most insightful collecting duos.

FIND YOUR LOVE

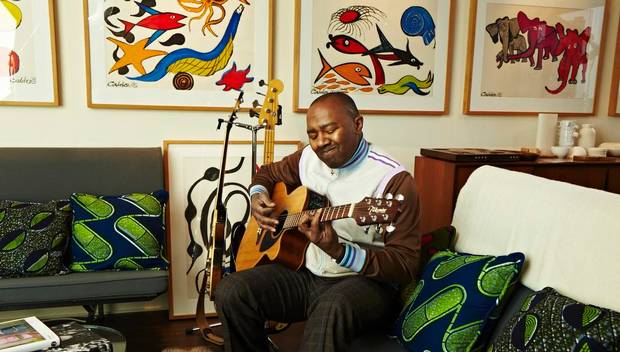

Kenneth Montague describes his 1970s upbringing as “kind of tri-cultural.” The child of Jamaican immigrants growing up near the Detroit border in Windsor, Ontario, he became appreciative of African-American culture. “I spent a lot of time watching Sanford and Son,” he says, “but I also made a lot of trips to the Detroit Institute of Arts with my mom.”

On one of those visits, when he was a 10-year-old boy, Montague fell in love with a photograph titled Couple in Raccoon Coats by James VanDerZee, depicting an elegant Harlem man and woman, clad in fur, before a gleaming Cadillac. “I thought, Wow, people lived like that,” says Montague. “I’m going to learn about photography.” Twenty years later, he called VanDerZee’s widow and bought a print of Couple in Raccoon Coats. It cost him over $10,000. Friends asked why he wasn’t investing that money. Montague’s answer: “This picture’s bringing me way more joy than talking about stocks.”

Montague began searching for other photographs about black identity in the late ’90s. He converted a portion of his home into gallery space to bring artists he admired, including the Jamaican-Canadian Michael Chambers and New Yorker Jamel Shabazz, “into the world.” Today he owns one of the biggest collections of images of black culture anywhere. Montague is also the founder and director of Wedge Curatorial Projects, a not-for-profit organization that creates gallery and museum shows centred around issues of identity.

While he continues to buy works that explore ideas of individuality and community, now Montague’s collecting purview has expanded beyond photography and painting to include design, music and fashion—new fields that have broadened his aesthetic mantra: “Put yourself into what you do.”

INVEST IN RELATIONSHIPS

“If you start looking at art as an investment, you are going the wrong way,” says Roy Heenan, offering counsel that’s worth careful attention. When he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1999, it was for both his remarkable legal career and his contribution to the Canadian art world, which includes a stint as chairman of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal as well as serving on the board of directors for several other visual arts institutions.

Heenan’s interest in art began in the early 1960s, when he happened upon an auction house near his office. Looking at its works, he discovered that art took his mind off “pretty tough industrial relations cases.” His collection took root once gallery visits became part of his routine and he came to know curators and gallery owners across Canada. Thanks to their guidance (supplemented by his own reading), he built his knowledge. “I really owe it to Andy Sylvester at Vancouver’s Equinox Gallery for introducing me to Gathie Falk, the renowned West Coast painter, sculptor and performance artist,” says Heenan. He gives equal credit to Pierre Théberge, a former National Gallery of Canada director, for igniting his love of the late London, Ontario, Regionalist painter and outspoken nationalist Greg Curnoe.

Heenan says things “really took off” once he became personal friends with many of the artists “and started buying major works”—a fact made clear whether you visit his law firm’s website or any of its nine Canadian offices. The first things you’ll see are jaw-dropping pieces of art. They are symbolic not only of Heenan’s identity, but its founder’s advice that when it comes to buying art, your key outlay is time spent building relationships.