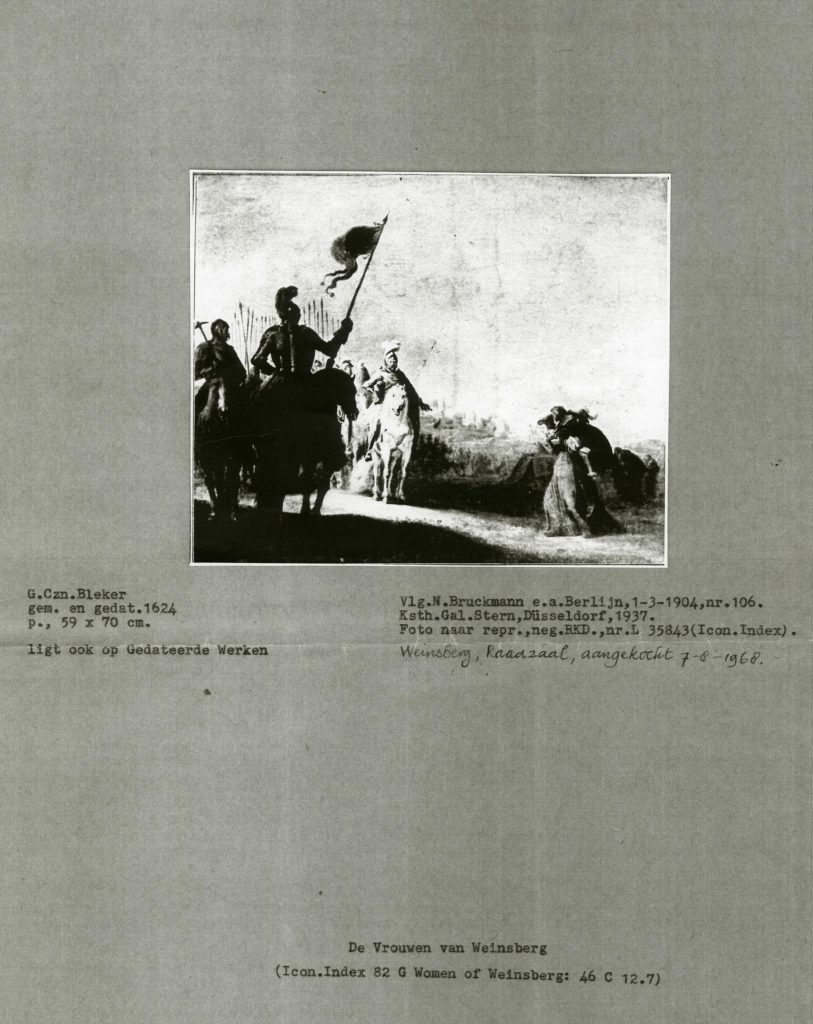

A detail from Women of Weinsberg by Gerrit Claesz Bleker (Dutch, 1592-1656), oil on canvas, 59 x 71cm. (Courtesy of the Max and Iris Stern Foundation)

The remarkable story of Max Stern’s Women of Weinsberg painting and its unusual recovery

A small German town, the Max Stern estate and how an art world diplomatic coup unfolded

—

To most of the art world, Women of Weinsberg, a seventeenth-century painting by the Dutch artist Gerrit Claesz Bleker is of unexceptional financial worth. In the German town of Weinsberg, however, it is an invaluable depiction of a foundational historical event and a defining act of female strength.

A work from the Dutch Golden age, Women of Weinsberg depicts an iconic moment in German history when King Conrad III of the Holy Roman Empire attacked the Bavarian city of Weinsberg and laid siege to its castle. As a measure of civility the king offered its women the opportunity to leave holding whatever they could. Foregoing all material belongings, they carried their husbands on their shoulders and their children under their arms. Moved by this display of wit and faithfulness, the king spared the lives of all Weinsberg citizens and set the city free.

It’s an iconic story, which is why almost 50 years ago, Weinsberg, a village with fewer than 12,0000 residents, bought Bleker’s painting from a private collector for its municipal gallery. Women of Weinsberg hung at the Weibertreu Museum for decades, until an inadvertent discovery proved that the work had been the property of one of Canada’s most famed art dealers, Max Stern, who ran his family’s gallery in Düsseldorf until 1937, when he fled the city after Nazi law (he was Jewish) forced him to sell over 300 paintings—including Women of Weinsberg.

Women of Weinsberg by Gerrit Claesz Bleker (Dutch, 1592-1656), oil on canvas, 59 x 71cm. (Courtesy of the Max and Iris Stern Foundation)

This finding about its prized art possession plunged a sleepy European village into a contemporary discussion of Nazi-era art looting, and of how Germany is handling this contentious matter. Now the painting has become the focus of an art-world diplomatic coup and an example of a win-win scenario in the complicated landscape of Holocaust-era restitution.

On May 7 international dignitaries travelled to Munich for a remarkable ceremony, one in which Women of Weinsberg was recovered by its rightful owners, the Max Stern estate. However, the Nazi-plundered painting will remain in the tiny German town that has been its home for nearly 50 years. As Stéphane Dion, Canadian ambassador and special envoy to the European Union and Europe, who was in attendance stated, it’s an instance of how “through the dedicated efforts of individuals and organizations, a small measure of justice can be brought to [a] dark period of history.”

Women of Weinsberg appeared on the radar of the Max Stern estate in 2014, entirely by chance. Philip Dombowsky, the archivist of the National Gallery of Canada’s Max Stern papers, was doing research at the Netherlands Institute for Art History in The Hague when he found a series of letters between Stern and a former director of the institute, Hans Schneider.

In one letter from October 1935, Stern wrote Schneider that he was forced “to liquidate our company” and “look for a different means of existence.” Not long after, Stern sent Schneider a black-and-white photograph of Women of Weinsberg along with a letter detailing his ownership of the painting that he would soon have to sell. The Netherlands Institute mounted the image on a piece of cardboard, over time adding annotations about the painting’s whereabouts. That is how Dombowsky traced the painting from Stern’s gallery to Weinsberg.

No one knows exactly how or when Women of Weinsberg left Stern’s hands, though at today’s restitution ceremony German officials explained that the decision was not his choice. Despite Nazi orders to halt his professional activity, Stern fought in court from 1935 to 1937, to keep his Düsseldorf gallery open “under all circumstances,” as he later wrote in his unpublished autobiography; he knew that “one day Hitler would be defeated.”

Annotated record from the Netherlands Institute for Art History (The Hague) of Women of Weinsberg by Gerrit Claesz Bleker. Courtesy of the Netherlands Institute for Art History (The Hague). (Courtesy of the Max and Iris Stern Foundation)

On September 13, 1937, however, Stern received notice that as a “Nichtarier” (not-Aryan), his professional accreditation to deal art was officially revoked. The decision was not one that he could appeal. He had four weeks to sell or dissolve his gallery. In November Stern placed the inventory of his family’s business up for sale at the Nazi-approved auction house Lempertz, in Cologne.

When the Stern heirs shared this story with officials in Weinsberg, the city acted cooperatively, allowing an examination of Women of Weinsberg. A Galerie Stern inventory stamp was found on the back on the painting, and representatives of the estate told the city that they hoped to restitute the painting. “It was a lot of information for the city to process,” says Willi Korte, the lead investigator for the Stern heirs. “They had never experienced such a claim and had no experience dealing with Nazi-era spoliated art.”

From a legal point of view, Weinsberg officials could have ignored the situation. Germany has no set laws outlining how to deal with Nazi-era claims, and its civil code states that property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it is lost or stolen. The door to restituting Holocaust-era lost art through German courts thus closed in 1975. Although Germany voluntarily signed the international agreement known as the Washington Principles of 1998, in which 44 countries committed to the restitution of art stolen or sold under Third Reich duress, the pact is legally non-binding.

This explains how, within one country, two cities—Weinsberg and Düsseldorf—have addressed claims from Stern’s heirs with dramatically divergent responses. Late last year Düsseldorf became the subject of a heated art-world scandal after its mayor cancelled a major exhibition on Max Stern, to have opened at the city’s Stadtmuseum earlier this year, and then re-instated the show but intervened in its curatorial direction to make it less Canadian.

In fact, the restitution ceremony for Women of Weinsberg was supposed to have taken place in Düsseldorf, to coincide with that exhibition. After the recent controversy, however, the venue was moved to the Neumeister auction house in Munich, a neighbouring city of Weinsberg.

Weinsberg’s open-minded approach to art restitution is a profound and celebrated contrast to what the Stern heirs have been facing. Says Clarence Epstein, director of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, “Weinsberg cooperated with us out of a moral obligation, not out of legal necessity. In doing so, they took an entirely different stance from Düsseldorf. ”

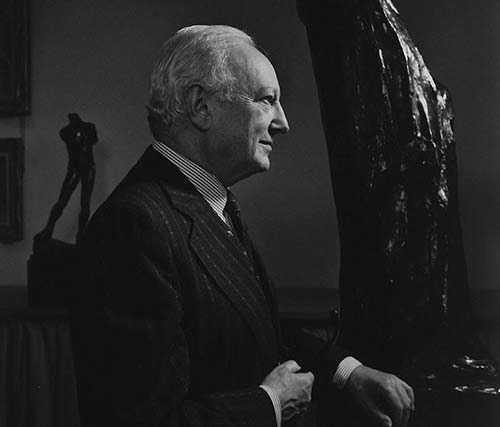

Max Stern by Yousf Karsh, 1973. (Courtesy of the Max and Iris Stern Foundation)

Since 2002 Epstein has played a key role at the helm of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, which was established in Stern’s memory. Although Stern never talked about his losses in Nazi Europe, after his death, his heirs, Montreal’s Concordia and McGill Universities, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem founded the organization, which today is an internationally renowned initiative investigating Holocaust-era cultural theft.

Its aim is to reclaim his art, no matter the current market worth. (Women of Weinsberg is as Willi Korte puts it, “a painting of a modest five-figure value.”) This counters a notion often fed by media that money rather than moral rectitude is at the heart of Holocaust-era restitution. Moreover, revenues from the sale of works the Stern Project recovers are placed back into the organization, which seeks to achieve mutually beneficial means to complicated situations.

In the case of Women of Weinsberg, city officials sought the advice of state and federal authorities including Germany’s Office for Provenance Research of the German Lost Art Foundation. In the end, two donors—the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States, and the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation—offered to compensate the Stern heirs for the loss of the painting.

In turn, recognizing the painting’s importance to the town, the Stern heirs decided that the treasured work, which Weinsberg bought in good faith, should remain there. In a sense, the town is re-purchasing Women of Weinsberg, this time with the blessing of its erstwhile owner’s heirs. Said Stefan Thoma, mayor of Weinsberg, “Our city is thankful that with the active support of foundations and donors, we were able to acquire the painting.”

So Women of Weinsberg will continue to hang in the Weibertreu Museum—with one important change: Now the label for the painting notes that Max Stern once owned it and the reason he lost it. This small but essential gesture is at the heart of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, explains Epstein: “It places Stern and all other Jews who were expunged from German history back into the country’s cultural narrative.” As for Weinsberg, the city’s reputation for virtue, like its clever twelfth-century women citizens’, will unquestionably grow as it becomes even better known as a place where imagination, reason and cooperation pave a path to justice.

The Dusseldorf Stadtmuseum announced its plans for an exhibition about Max Stern in April, 2014, at a restitution ceremony in the gallery, where it returned to the Stern estate the painting Self-Portrait of the Artist by the 19th-century Romantic artist Wilhelm von Schadow. Five years earlier, in 2009, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project had discovered the work in the inventory of the museum. The painting had been listed as one of the items in the 1937 catalogue for the forced auction at Lempertz.

At the ceremony at the Stadtmuseumwhere the painting was returned to Stern's estate, Susanne Anna announced that under her direction the museum would organize an exhibition to acknowledge the Galerie Stern's importance to the city of Dusseldorf, because the Third Reich had erased its history, as well as the stories of the city's other Jewish art dealers. She explained the show was necessary as a reminder that "art was only one thing stolen by the Nazis. They took everything – rugs, bicycles, cars, carpets, candlesticks and books – turning Germany into a garage sale of Jewish goods to finance the war."

What Anna left out of her speech, however, was the highly arduous process that the Stern heirs had faced in reclaiming Self-Portrait of the Artist, one that took five years in a city known for its conservative values.

"It was complicated," Epstein says, "because Germany has no set laws outlining how to deal with claims." Moreover, the country's civil code states that property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it was lost or stolen. Thus, the door to restituting works through German courts was shut in 1975. While Germany is among 44 countries that voluntarily signed the Washington Principles of 1998, committing itself to the restitution of art stolen by the Nazis or sold under duress, the pact is legally non-binding.

Although Anna was sympathetic to seeing the painting's return, "the matter was not one for her to decide," Epstein says, "because the work was municipal property." In 2010, to fight the Stern estate's claim for Self-Portrait of the Artist, Dusseldorf city council hired lawyer Ludwig von Pufendorf, who had recently become one of Germany's most outspoken critics of art restitution after the Berlin state senate released Berlin Street Scene by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner from Berlin's Bruecke Museum in 2006. The restitution of the painting, which had been the centrepiece of the museum's collection for 26 years, ignited controversy across the European art world.

Anita Halpin, a granddaughter of the Jewish-German art collectors Alfred and TeklaHess, claimed Kirchner's expressionist masterpiece after a lengthy process in which her legal representatives presented evidence that under anti-Semitic persecution, two Gestapo agents forced her grandmother to part with the painting in 1936. Disputing Halpin's claim that Berlin Street Scene was sold under Nazi duress, vonPufendorf, then president of the Bruecke Museum's patrons' association, publicly railed against the decision and called for a parliamentary inquiry into whether the restitution contract was binding.

The uproar escalated and spread when in the fall of 2006, Halpin sold the painting at Christie's New York for $38.1-million (U.S.). Bernd Schultz, then director of the Berlin auction house Villa Grisebach, called the Kirchner return a "betrayal of the German nation." In London, Royal Academy director Sir Norman Rosenthal argued that museums should not be forced to restitute Nazi-looted artwork and that it was a practice that makes the rich richer. Guardian columnist Jonathan Jones wrote that restituting "paintings from the cities where they have the deepest relevance is meaningless and contrary to the public good."