“You have to have really nimble fingers to work with porcelain, because it just wants to crack, bend and blow up.”

—Shary Boyle

Not your grandmother’s porcelain

Shary Boyle’s very personal art straddles the worlds of Vermeer and Feist.

—

In 1912 the surrealist artist Marcel Duchamp famously declared that painting was dead, in response to the ease with which images could be made using photography and other new technologies. His words marked the start of a 20th-century trend in which art became increasingly incomprehensible, as the brainy ideas behind a creative work trumped beauty or its maker’s skill.

Which makes Shary Boyle, 38, who last month won the $25,000 Hnatyshyn Award for outstanding achievement by a Canadian artist, something of an oddball. Not only is Boyle a virtuoso whose technical abilities could match the 17th-century master Vermeer, her art is personal in an era that favours global meaning, figurative in a world of abstraction, born of emotion instead of cool concepts, of a decidedly female viewpoint in a male-dominated industry, and made from age-old materials like paint and porcelain rather than more trendy mediums such as video.

Yet Boyle is arguably Canada’s most celebrated artist of recent years. Before winning the Hnatyshyn, she was twice a finalist for the Sobey Art Award, which celebrates an artist under 40; she won the 2009 Gershon Iskowitz Prize for a successful artist in mid-career; and she is the focus of two acclaimed exhibitions:Breaking Boundaries, with three other ceramic artists at Toronto’s Gardiner Museum, and Flesh and Blood, a three-city solo show, which opened last week in Montreal.

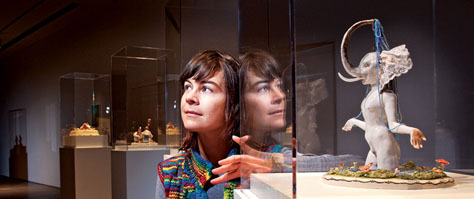

The most enthusiastic applause has been for Boyle’s porcelain figures, painstakingly assembled works—like the six-armed, multi-eyed female creature whose many hands weave a star-shaped web in Untitled. “You have to have really nimble fingers to work with porcelain,” says Boyle, who mastered her craft studying the techniques of such European porcelain houses as Sèvres and Meissen, “because it just wants to crack, bend and blow up.”

Critics have lauded not only Boyle’s method but her characters that cleverly refashion archetypes from fables and myths, while incorporating symbolic elements of a new feminist language. It creates a tension between the figures’ seductive forms and their heavy subject matter, which simultaneously enchants and unsettles viewers, giving her art what she calls “a confrontational insistence.”

These qualities captivated Louise Déry, director of Montreal’s Université du Québec à Montréal Gallery, when she saw Boyle’s porcelains in 2006. She seized upon something no other curator seems to have yet noticed. “I was struck by Shary’s ability to move from one medium to another,” says Déry, explaining how Boyle’s work in drawing, painting and performance art—including illustrations for publications like the cult comic-book anthology Kramers Ergot and audio-visual collaborations with indie music scene darlings Peaches and Feist—were as much a part of her art as her porcelains.

Déry commissioned Flesh and Blood to give an overview of Boyle’s talents. As its title suggests, the exhibition is a meditation on family, and all its messy complexities. It features trademark Boyle porcelains like The Bed where a man and woman slumber seemingly unaware of a headless figure at their side—a haunting reminder that no couple sleeps alone. Flesh and Blood also introduces Boyle’s first-ever collection of large-scale sculptural works, including the installation When the Bough Breaksin which a hand-modelled ceramic infant is thrown headfirst out of a cradle, a metaphor of Western consumption. “I sometimes use children as symbols of hunger—they have so many needs,” says Boyle.

Explains Boyle’s dealer Jessica Bradley, “She will say the things we don’t dare talk about.” But Boyle is clear her intention is not to shock but to create an alternate vision where even the darkness of humanity is made “magical and beautiful.” In a catalogue for Flesh and Blood, Déry coins the phrase “redemption of the senses” to describe Boyle’s creative quest. “Although for decades,” says Déry, “it’s been predicted that technology-based media would sidetrack traditional arts, we are now seeing a desire for work that takes emotion off the back burner.” If Marcel Duchamp were alive to see Shary Boyle, he would no doubt agree.