Ships in Distress on a Stormy Sea by Jan Porcellis is the 14th recovery for the Max Stern Restitution Project.

Montreal Project Helps Solve Issue Around Recovering Nazi-Stolen Art

Canada’s Max Stern Restitution Project forges new ground in an issue that’s roiled the art market for decades.

—

This week, at a landmark ceremony at the Canadian embassy in Berlin, Montreal’s Max Stern Restitution Project not only recovered two Dutch Old Masters paintings – Ships in Distress on a Stormy Sea by Jan Porcellis and Landscape with Goats by Willem Buytewech the Younger – it announced a solution for one of the most problematic questions surrounding Nazi-looted art: How do you ask for the return of a plundered work from a party that innocently came to own it?

Hitler’s Third Reich systematically looted art on such a scale that Holocaust-spoliated cultural property remains an unresolved topic, as spotlighted by the 2013 discovery of more than 1,500 works – many owned by persecuted Jews – hidden for decades by Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a Nazi art dealer.

The passage of time has complicated the return of Nazi-plundered cultural property. Several generations after their theft, works of art of questionable provenance have often passed through several hands. Current possessors who paid for pieces in good faith “feel an injustice is being done to them when they are asked to give it up to the original owner or his heirs,” says Wesley Fisher, director of research for the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

This complex issue was at the heart of why the Max Stern Restitution Project – created to find and recover spoliated paintings more than 50 years after they were lost – revealed this week that it will provide German tax receipts for the entire market value of the art it recovers in Germany. This will compensate “people who don’t have any responsibility for the stolen work of art they own,” says Clarence Epstein, director of the Stern Restitution Project.

From left, Guenter Stock, president of German Friends of Hebrew University; Marie Gervais-Vidricaire, Canada’s ambassador to Germany; Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly, Clarence Epstein of the Stern Restitution Project and Susanne Anna a museum director mark the recovery of two paintings on Monday in Berlin.

It’s an unprecedented solution that’s been a decade in the making. The Stern Restitution Project, named for the famous Montreal art dealer who died in 1987, is the only operation of its kind in the world. A not-for-profit organization run out of Concordia University, one of Stern’s three heirs, along with McGill and Hebrew Universities, the project has no time limit nor monetary incentives when recovering art other than to further the understanding of restitution. It addresses the fact that most Nazi-era looted artworks were not exorbitantly priced masterpieces like Gustav Klimt’s Woman in Gold. This counters a notion often fed by media that money rather than moral rectitude is at the heart of Holocaust-era restitution. Revenues from the sale of works the Stern Project recovers are placed back into the organization.

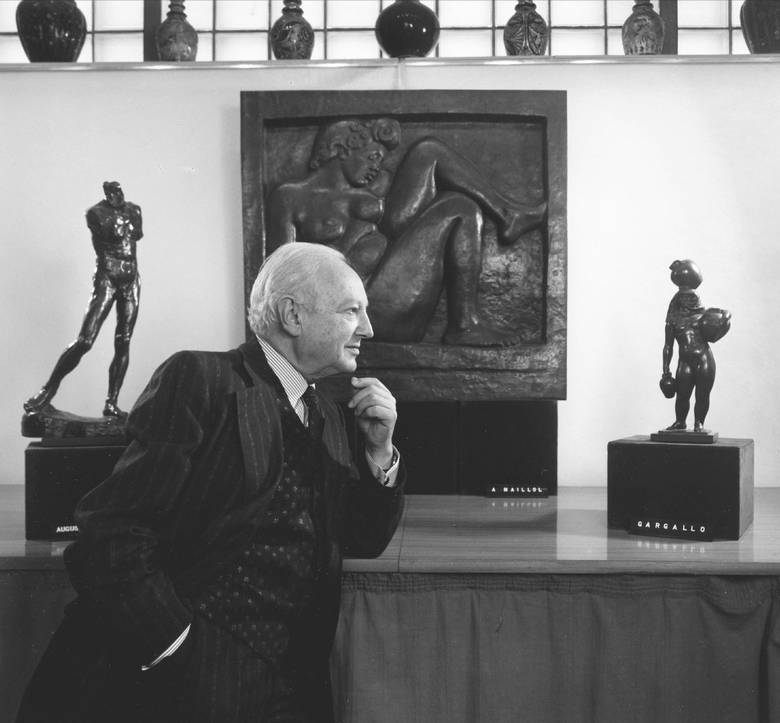

The project’s goal is to put Max Stern and other Jewish art dealers expunged from history back into the cultural narrative. In Canada, Stern became renowned as the formidable owner of Montreal’s Dominion Gallery, which played a key role in the careers of such Canadian painters as Emily Carr and Paul-Émile Borduas, and represented international masters including Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore and Auguste Rodin.

Until a decade ago, it remained unknown that Stern had a previous life in Duesseldorf, which came to an end in 1937 when the Nazis forced him to liquidate the inventory of his family’s esteemed Rhine Valley art dealership in sale No. 392 at the Cologne-based, Nazi-approved Lempertz auction house (still in business today).

Max Stern was renowned owner of Montreal’s Dominion Gallery, which played a key role in the careers of such Canadian painters as Emily Carr and Paul-Émile Borduas.

Third Reich laws deemed that Stern was incapable of promoting German culture as a Jew. Despite successfully reinventing himself, Stern never discussed the circumstances of his early life, including that he never saw a cent from the Lempertz sale because its proceeds were ransomed to obtain his mother’s exit visa. To break this silence, Stern’s executors set out “to meaningfully address his loss,” Epstein says.

This week’s restitution of Ships in Distress on a Stormy Sea and Landscape with Goats marks the Stern estate’s 14th and 15th recoveries. It also highlights what the organization’s lead investigator Willi Korte describes as the project’s “lack of achievement when seeking the support of German auction houses to restitute art until now.”

Although the project has recovered works found in the United States, the Netherlands, Spain and Germany, the majority of Stern’s paintings have come to light via the German art trade. Since the country’s civil code states that property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it was lost or stolen, the door to restituting works through German courts was shut in 1975. As a result, art recoveries by the Concordia-based organization have followed a series of carefully planned measures, including placing every painting in the 1937 Lempertz catalogue on Interpol – the first organization of its kind to take this step.

As well, in 2006 it curated the art exhibition Auktion 392: Reclaiming the Galerie Stern Duesseldorf, long before the whereabouts of any Stern paintings were known. The “ghost exhibition,” which displayed black-and-white reproductions of works that Stern was forced to sell at auction, included stops in Montreal, New York, London and Jerusalem. It made Stern’s private story public and part of the international art-world conversation – “that Nazi-looted art was the last prisoner of war,” in the words of Epstein.

Landscape with Goats by Willem Buytewech the Younger.

Yet for every advance made by the Stern project, there have been steps backward. In 2005, it unsuccessfully approached auction houses in Berlin and Cologne with claims for works which Stern lost under Nazi duress. “In refusing to help us find a solution,” says Korte, “these dealers felt justified because they were following the law.”

This week’s restitution ceremony was “entirely atypical” says Epstein, because its two Dutch Masters paintings were returned thanks to unprecedented co-operation of two auction houses: Metz in Heidelberg and Stahl in Hamburg. In part this is because the German art trade is shadowing the lead of international auction houses Sotheby’s and Christie’s, which realized more than a decade ago that selling objects with a tainted provenance is ethically questionable and a potential public-relations disaster. It is also following the practice of German public museums, which in recent years have facilitated a significant number of restitution claims.

Still, according to Epstein, the Stern project “needed to figure out a state-sanctioned and just solution to compensate people who returned a Stern piece which they came to own innocently.” To this end, several years ago the organization began plans to grant tax receipts for the current market value of spoliated pieces returned to Stern’s estate. They first approached the German government “but the discussion went back and forth for years without creating any results,” says Epstein. The arrangement came to fruition last month when the German Friends of the Hebrew University, a Berlin-based charity, and an affiliate of the Stern Project, established that it could accept paintings on behalf of the Stern estate and offer donation receipts in return.

The effectiveness of this novel measure remains to be seen, as it takes effect in 2017. German owners of Stern’s spoliated art may decide against the tax incentive and either hold on to art belonging to them, or sell it, both legally permitted options. However, as Wesley Fisher explains, while there have been other similar proposals over the years for various types of tax breaks, the Stern program with the Friends of the Hebrew University “is the first large-scale implementation of such an idea.”

In what has been a historically fraught situation, a credible solution finally exists to help right the wrongs of the past.