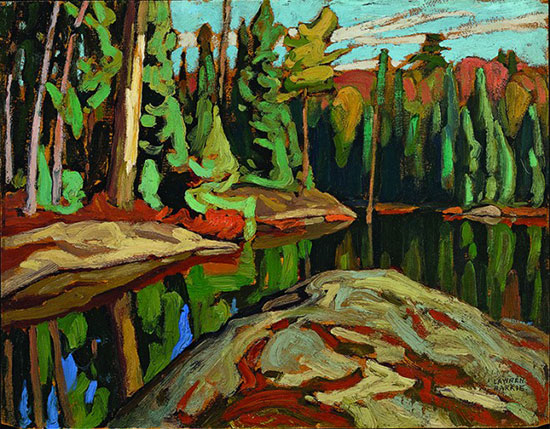

“Algoma” by Lawren S. Harris. Courtesy of McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

How Comedian Steve Martin became a Champion for Lawren Harris

Now, the Group of Seven artist will finally get his wish.

—

With his austere, arresting and spiritually charged paintings of icebergs, lakes and mountains, Lawren Harris became famous for his iconic images of Canada and the leader of our most influential art movement, the Group of Seven. But this wasn’t the legacy he dreamed of. For the better part of his career, Harris wanted to move beyond landscapes to make his name with work that contributed to modern art movements beyond the nation’s border. Although this goal eluded Harris while he was alive, now, 40 years after his death, it may be realized.

After decades of curatorial silence on the painter, Harris will become the focus of three separate shows over the next three years, starting next week with the opening of the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition Lawren Harris: Canadian Visionary. The exhibits, including one that will be curated by the American comedian and author Steve Martin, will put Harris in the international spotlight and offer fresh takes on his art, bringing new audiences to the national legend, in both the U.S. and Canada.

From Los Angeles, Martin explains how he first became interested in the painter’s work. A long-time collector of modern masters, he believes he first stumbled upon Harris’s painting in an auction catalogue. “Being an American,” laughs Martin, “I thought he was an unknown artist. Little did I know that he was Canada’s greatest painter.” Struck by Harris’s unique ability to render landscape “in a non-European way,” Martin added to his impressive collection (which includes such 20th-century giants as Pablo Picasso, Georges Seurat and Edward Hopper) three works by Harris.

Last summer, one of these captivated Ann Philbin, director of L.A.’s Hammer Museum, while she was having dinner in Martin’s home. “She was so knocked out,” says Martin, that she invited him to co-curate a Harris exhibition for the Hammer, to open in 2015. (It will then travel to other North American venues, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, where Martin is working with Andrew Hunter, the curator of Canadian art.) At first, Martin declined, professing a lack of expertise. But he changed his mind. “The only person I’ve met in America who knows about Lawren Harris is the writer Adam Gopnik,” he says. “And he’s Canadian. This is a real hole in America’s artistic knowledge.”

As a painter who tried to position his work within the broad context of early-20th-century modernism, Harris would have been grateful for such a champion. Heir to the fortune of farm-machinery manufacturer Massey-Harris Co. Ltd., Harris had the means and interest to set out for Berlin in 1904, after attending the University of Toronto. He spent four years in Europe, where he likely first became acquainted with cutting-edge, non-objective, spiritual art, including the work of Wassily Kandinsky. Upon his return to Canada, Harris struck up a friendship with painters Tom Thomson and J.E.H. MacDonald and, in May 1920, he played a crucial role in the opening of the first exhibition of the Group of Seven.

Cosmopolitan, talented, well-educated and elegant—he famously wore a three-piece suit to the studio—Harris was the perfect patrician voice to lead the charge for Canadian art throughout the ’20s. And he did, creating his most famed works during this period: highly stylized and spine-chilling images of the nation’s skylines, mountains, lakes and forests, and landscapes. The paintings became emblems of national identity, but what few people knew is that Harris, like Georgia O’Keeffe and Marsden Hartley south of the border, hoped to forge a continental approach to landscape painting distinct from European impressionism, the dominant style of the day.

In 1926, Harris stepped into this conversation formally when his painting Northern Lake won a gold medal at Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial International Exposition, where New York culture maven Katherine Dreier was compelled to take a second look at his art. Dreier invited Harris to join her newly formed Société Anonyme, an organization she co-founded with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp to promote avant-garde art, in the context of conservative postwar tastes. The group’s sole Canadian representative, Harris participated in its show The International Exhibition of Modern Art, where his canvases hung alongside those by such greats as Picasso, El Lissitzky, Arthur Dove and O’Keeffe.

Harris’s landscapes now grew increasingly non-representational. By the late ’20s, he’d turned away from the style that made him famous and advocated on behalf of abstract art. It was a move so controversial that it played out in the press and brought Harris’s art-making to a near standstill by 1930. To complicate matters, a few years later, he left his wife of 24 years to marry Bess Housser, the spouse of a close boyhood friend. On the lam from wagging Toronto tongues, the couple relocated, first to New Hampshire, where Harris took a position at Dartmouth College, then to Santa Fe in the spring of 1938.

Were it not for financial impediments, says Andrew Hunter, Harris “would never have come home.” But restrictions at the outbreak of the Second World War made it impossible for him to transfer funds from Canada, so, in 1940, he and Bess resettled in Vancouver. “I think he would have had a different role, had he stayed in the States,” says Hunter. “He wanted to be part of what was going on there.”

Away from Canada, Harris had the desire to pick up his brushes again, and the confidence to make art that was a world away from his Group of Seven canvases. In New Mexico, along with Americans Emil Bisttram and Raymond Jonson, he became a member of the Transcendental Painting Group, dedicated to abstract paintings of colour, light and design.

Several of these, including Abstract No. 7 (1939)—a panoply of orange and blue geometric forms that Harris presents with the same icy intensity as his northern landscapes—will be part of the Vancouver Art Gallery’s exhibition. Not only is it the first Harris show mounted by a major institution in almost 30 years, it offers an unprecedented view of the artist’s oeuvre in its totality. Featuring more than 80 works owned by the VAG, it charts the arc of Harris’s career up to 1967, when he stopped painting, and includes such little-known canvases as paintings of lumber camps in Wisconsin done in 1909 as potential illustrations for Harper’s magazine, and works on paper that have never been seen by the public.

“There’s a tendency to want to deal with the first half of his career and not the abstracts,” says the exhibition’s organizer, Ian Thom, art historian and VAG senior curator. “But Harris spent more time dealing with abstracts than he did with landscapes.” Only by seeing the entirety of his work, he explains, can Harris be understood as “a painter who kept pushing himself.”

In 2016, scholar and curator Roald Nasgaard will present another broad take on Harris, in the provisionally titled show Mystical Modernism, which will be launched at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. The exhibition will focus on the artist’s post-Group-of-Seven painting from the early ’30s to 1945. “Harris’s abstract painting is a little weird, personal and eccentric,” says Nasgaard. “It seems to happen out there in left field, apart from the main modernist trajectory. But if you look at the work in the context of his North American contemporaries, it has all sorts of parallels and he hardly stands alone.”

Nasgaard will present the painter alongside artists such as O’Keeffe—whose histories have been told without any mention of Harris. When Harris returned to Canada, Vancouver was the Siberia of the world art scene, the furthest thing from the international cultural mecca it has become today. Until his death in 1970, Harris played a key role in the city’s development, advocating on behalf of younger artists and giving them “permission to be more adventurous in how they made their work,” says Thom. But there was little fanfare for the abstract art that he continued to make while his ties south of the border faded.

People wanted Harris for a “nationalist, kitschy notion of Canada” says Hunter. The postwar climate was nostalgic and “he was sucked back into talking about the Group of Seven and his work in the ’20s.” Overexposed in the spotlight, the very paintings that made his name came to be criticized as formulaic, illustrative clichés of Canada.

But Martin has a different take. His exhibition concentrates exclusively on the best 30-odd pieces Harris made during the ’20s, art he describes as “master works,” made by a painter at the height of his career. Martin is confident they will be enough to entice American viewers. Although Canadians may see them as symbols of the nation, he says, they stand up to the best American art made during the same period. “Ultimately,” he says, “I hope—and I think—the work is just going to slay everyone.”

With his austere, arresting and spiritually charged paintings of icebergs, lakes and mountains, Lawren Harris became famous for his iconic images of Canada and the leader of our most influential art movement, the Group of Seven. But this wasn’t the legacy he dreamed of. For the better part of his career, Harris wanted to move beyond landscapes to make his name with work that contributed to modern art movements beyond the nation’s border. Although this goal eluded Harris while he was alive, now, 40 years after his death, it may be realized.

After decades of curatorial silence on the painter, Harris will become the focus of three separate shows over the next three years, starting next week with the opening of the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition Lawren Harris: Canadian Visionary. The exhibits, including one that will be curated by the American comedian and author Steve Martin, will put Harris in the international spotlight and offer fresh takes on his art, bringing new audiences to the national legend, in both the U.S. and Canada.

From Los Angeles, Martin explains how he first became interested in the painter’s work. A long-time collector of modern masters, he believes he first stumbled upon Harris’s painting in an auction catalogue. “Being an American,” laughs Martin, “I thought he was an unknown artist. Little did I know that he was Canada’s greatest painter.” Struck by Harris’s unique ability to render landscape “in a non-European way,” Martin added to his impressive collection (which includes such 20th-century giants as Pablo Picasso, Georges Seurat and Edward Hopper) three works by Harris.

Last summer, one of these captivated Ann Philbin, director of L.A.’s Hammer Museum, while she was having dinner in Martin’s home. “She was so knocked out,” says Martin, that she invited him to co-curate a Harris exhibition for the Hammer, to open in 2015. (It will then travel to other North American venues, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, where Martin is working with Andrew Hunter, the curator of Canadian art.) At first, Martin declined, professing a lack of expertise. But he changed his mind. “The only person I’ve met in America who knows about Lawren Harris is the writer Adam Gopnik,” he says. “And he’s Canadian. This is a real hole in America’s artistic knowledge.”

As a painter who tried to position his work within the broad context of early-20th-century modernism, Harris would have been grateful for such a champion. Heir to the fortune of farm-machinery manufacturer Massey-Harris Co. Ltd., Harris had the means and interest to set out for Berlin in 1904, after attending the University of Toronto. He spent four years in Europe, where he likely first became acquainted with cutting-edge, non-objective, spiritual art, including the work of Wassily Kandinsky. Upon his return to Canada, Harris struck up a friendship with painters Tom Thomson and J.E.H. MacDonald and, in May 1920, he played a crucial role in the opening of the first exhibition of the Group of Seven.

Cosmopolitan, talented, well-educated and elegant—he famously wore a three-piece suit to the studio—Harris was the perfect patrician voice to lead the charge for Canadian art throughout the ’20s. And he did, creating his most famed works during this period: highly stylized and spine-chilling images of the nation’s skylines, mountains, lakes and forests, and landscapes. The paintings became emblems of national identity, but what few people knew is that Harris, like Georgia O’Keeffe and Marsden Hartley south of the border, hoped to forge a continental approach to landscape painting distinct from European impressionism, the dominant style of the day.

In 1926, Harris stepped into this conversation formally when his painting Northern Lake won a gold medal at Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial International Exposition, where New York culture maven Katherine Dreier was compelled to take a second look at his art. Dreier invited Harris to join her newly formed Société Anonyme, an organization she co-founded with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp to promote avant-garde art, in the context of conservative postwar tastes. The group’s sole Canadian representative, Harris participated in its show The International Exhibition of Modern Art, where his canvases hung alongside those by such greats as Picasso, El Lissitzky, Arthur Dove and O’Keeffe.

Harris’s landscapes now grew increasingly non-representational. By the late ’20s, he’d turned away from the style that made him famous and advocated on behalf of abstract art. It was a move so controversial that it played out in the press and brought Harris’s art-making to a near standstill by 1930. To complicate matters, a few years later, he left his wife of 24 years to marry Bess Housser, the spouse of a close boyhood friend. On the lam from wagging Toronto tongues, the couple relocated, first to New Hampshire, where Harris took a position at Dartmouth College, then to Santa Fe in the spring of 1938.

Were it not for financial impediments, says Andrew Hunter, Harris “would never have come home.” But restrictions at the outbreak of the Second World War made it impossible for him to transfer funds from Canada, so, in 1940, he and Bess resettled in Vancouver. “I think he would have had a different role, had he stayed in the States,” says Hunter. “He wanted to be part of what was going on there.”

Away from Canada, Harris had the desire to pick up his brushes again, and the confidence to make art that was a world away from his Group of Seven canvases. In New Mexico, along with Americans Emil Bisttram and Raymond Jonson, he became a member of the Transcendental Painting Group, dedicated to abstract paintings of colour, light and design.

Several of these, including Abstract No. 7 (1939)—a panoply of orange and blue geometric forms that Harris presents with the same icy intensity as his northern landscapes—will be part of the Vancouver Art Gallery’s exhibition. Not only is it the first Harris show mounted by a major institution in almost 30 years, it offers an unprecedented view of the artist’s oeuvre in its totality. Featuring more than 80 works owned by the VAG, it charts the arc of Harris’s career up to 1967, when he stopped painting, and includes such little-known canvases as paintings of lumber camps in Wisconsin done in 1909 as potential illustrations for Harper’s magazine, and works on paper that have never been seen by the public.

“There’s a tendency to want to deal with the first half of his career and not the abstracts,” says the exhibition’s organizer, Ian Thom, art historian and VAG senior curator. “But Harris spent more time dealing with abstracts than he did with landscapes.” Only by seeing the entirety of his work, he explains, can Harris be understood as “a painter who kept pushing himself.”

In 2016, scholar and curator Roald Nasgaard will present another broad take on Harris, in the provisionally titled show Mystical Modernism, which will be launched at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. The exhibition will focus on the artist’s post-Group-of-Seven painting from the early ’30s to 1945. “Harris’s abstract painting is a little weird, personal and eccentric,” says Nasgaard. “It seems to happen out there in left field, apart from the main modernist trajectory. But if you look at the work in the context of his North American contemporaries, it has all sorts of parallels and he hardly stands alone.”

Nasgaard will present the painter alongside artists such as O’Keeffe—whose histories have been told without any mention of Harris. When Harris returned to Canada, Vancouver was the Siberia of the world art scene, the furthest thing from the international cultural mecca it has become today. Until his death in 1970, Harris played a key role in the city’s development, advocating on behalf of younger artists and giving them “permission to be more adventurous in how they made their work,” says Thom. But there was little fanfare for the abstract art that he continued to make while his ties south of the border faded.

People wanted Harris for a “nationalist, kitschy notion of Canada” says Hunter. The postwar climate was nostalgic and “he was sucked back into talking about the Group of Seven and his work in the ’20s.” Overexposed in the spotlight, the very paintings that made his name came to be criticized as formulaic, illustrative clichés of Canada.

But Martin has a different take. His exhibition concentrates exclusively on the best 30-odd pieces Harris made during the ’20s, art he describes as “master works,” made by a painter at the height of his career. Martin is confident they will be enough to entice American viewers. Although Canadians may see them as symbols of the nation, he says, they stand up to the best American art made during the same period. “Ultimately,” he says, “I hope—and I think—the work is just going to slay everyone.”