SATURDAY NIGHT - 07 / 14 / 2001

Four Nights in the Funhouse: Janet Cardiff and George Miller at the Venice Biennale

The most inventive and exciting Canadian project at the art show in years.

—

The Venice Biennale is as famous for its parties as for its prestigious art prizes. This year, a husband-and-wife team from Lethbridge took centre stage with a work that’s part sci-fi film, part murder mystery, part amusement-park ride

NEAR THE SOUTH END OF Venice’s Grand Canal, in the pale amber light of the early evening, waves sparkle and stir around the fifteenth-century Palazzo Pisani Moretta. Water taxis dock alongside the palace’s crimson-carpeted pier, as guests for tonight’s party are escorted out of the boats and down the narrow dock by black-tied greeters. As they walk through the palace’s massive crystal doors, they enter a hall of marble, mirrors, and dark wood panelling. There, they’re met with tall glasses of Proseco and jubilant accounts of the day’s events.

The three-day preview for Venice’s forty-ninth Biennale, the world’s most important platform for contemporary art, which runs from June 10 to November 4, began at noon. In advance of the event’s formal opening to the public, more than 20,000 curators, museum directors, critics, and art lovers have descended upon the city to tour both the island’s Arsenale district, where over 100 international artists are displaying their work, and the Giardini, a monumental park that houses thirty national pavilions, each featuring its country’s most promising artist. The Biennale, often called “the Olympics of the art world,” has long been the place to discover the next big star. Winning a prize means major recognition: when Robert Rauschenberg was awarded the grand prize in 1964, it not only boosted his career, it was also a turning point for American art. “Venice is not an art fair; it’s not about the commercialism of buying or selling,” says Marc Mayer, director of the Toronto contemporary-art gallery The Power Plant. “It‘s about putting your best face forward as a nation that produces great art. The thing about Venice is, the whole art world goes.”

Canada has participated at Venice since 1952, but none of its artists has ever received an award. The word at the Palazzo Moretta tonight, though, is that this year will be different. Canada is represented by the husband-and-wife duo Janet Cardiff and George Miller, already considered two of the most exciting artists of the moment. In March, Cardiff won critical acclaim and the $50,000 Millennium Prize for her Forty Part Motet, a hauntingly beautiful sound installation she produced, with Miller’s help. It featured nothing to look at other than forty speakers-Cardiff had recorded, separately, the forty vocal harmonies of a piece of classical music and arranged them in a way that allowed the audience to wander, in a sense, inside the sound. The effect was so powerful that audiences left the work in tears. For the Biennale, the couple has created The Paradise Institute, which is rumoured to be equally powerful. Part sound sculpture, part sci-fi video art, the work is a pioneering cinematic installation, far more ambitious in scope than Motet.

Whether or not they take home a prize, this year’s Canadian commissioner, Wayne Baerwaldt, of Winnipeg’s Plug In Gallery, who is responsible for producing and promoting the exhibit, is determined his artists – and the show he’s putting on – will not be forgotten. That’s why this crowd is gathered here at the Palazzo Moretta. “The Biennale is about creating a buzz,” he explains. Thanks to his charms, the Count Moretta has offered his palace for the evening’s celebration in honour of Cardiff and Miller, giving Canada one of the most exclusive addresses in Venice for its soiree. After cocktails on the piano terra, the party moves up two flights of sweeping red stairs for a formal dinner for 180. As guests enter the second-floor space they are bathed in the light of over a dozen baroque candle-lit chandeliers, which hang from a frescoed ceiling painted by the sixteenth-century Venetian master Tintoretto.

Sitting down for dinner, filmmaker Noam Gonick remarks, “Wayne is the reincarnation of Andy Warhol. Warhol called his interaction with critics, artists, buyers, and fundraisers, ‘social work.’ He was a master at it. Like him, Wayne is a natural.” Indeed, Baerwaldt spent the better part of the last year networking with the art cognoscenti to ensure that the palazzo would now be packed with the likes of Kasper Konig, the director of Cologne’s Ludwig Museum, Hans Ulrich Obrist from Paris’s Musee d’art moderne, James Lingwood of London’s Artangel, and Chrissie Iles, curator at New York’s Whitney Museum. Helping Baerwaldt along is an entourage of Plug In supporters, including the editors of Border Crossings magazine, Meeka Walsh and Robert Enright, and painter Eleanor Bond.

Throughout the four-course meal, which features an endless procession of Venetian delicacies, the talk is about how the couple will fare. “Janet and George have advanced the language of contemporary art,” the New York art dealer Roland Augustine offers. “With The Paradise Institute, they will prove that there isn’t an artist around who has taken the use of audio and pushed it as far as they have.” Stephane Aquin, of Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts, is more succinct: “Right now, it is Cardiff and Miller’s moment.”

Cardiff and Miller are less assured. The couple has enjoyed recent international recognition, but they are a long way from being household names. Until last year, when Cardiff won a scholarship funded by the German government that took the pair to Berlin, they worked in near isolation in Lethbridge, Alberta. They offer few words at the evening’s speeches. “You work and edit and you have no idea of how people will respond,” Miller explains later. “There’s no telling whether people will like it or not. In Venice, there’s an intensity of being in front of the world, of having to perform. It’s scary.” “When we found out that we had been selected to come here,” Cardiff adds, “we knew that we wanted to do this piece. But we also knew that it might not work. The Paradise Institute is an experiment.” Miller finishes off her sentence: “Totally.”

Baerwaldt has no such doubts. To be certain that word of their work spills out of the palazzo this evening and onto the streets of Venice, he has planned an after-dinner party, to which everyone is invited. Once dessert is served, his guests return to the palazzo’s main floor, where the flamboyant Berlin-based band Fuzzy Wuzzy Lovin’ Cup Explosion begins to play. The event is listed by the hip London art magazine Frieze in the mobile-phone updates it sends out to wired Biennale-goers. The message is out: “Palazzo Moretta: All are welcome at Canada.”

By midnight, the palazzo is so crowded that it is difficult to move across the floor, much less dance. With each passing hour, the energy intensifies until the soiree hits a rave-like pitch somewhere in the early morning. The two people at the centre of all this, though, have retired for the night. It’s too early for them to celebrate.

IT SHOULD COME AS NO SURPRISE to anyone who’s seen their work that Cardiff, who’s forty-four, and Miller, who’s forty, count the 1930s novelist Dashiell Hammett among their heroes. In his novel The Thin Man, Hammett created Nick and Nora Charles, the glamorous and intrepid husband-and-wife duo who solve mysteries between wisecracks and martinis. Ever since Cardiff and Miller met, almost twenty years ago, they, like the fictitious Nick and Nora, have seen their work as an all-consuming passion that relies on the power of their partnership.

The roots of their work stretch back to the seventies and the farmhouse in Brussels, Ontario, where the red-headed Cardiff grew up. Her interest in sounds and environments began when she was a child. She remembers the vividness of noises she heard after dusk, as she did barnyard chores. “When something moves at night, in the dark, you are highly aware of it,” she observes. Years later, audio would creep into her art, and ultimately take it over.

Cardiff trained as an artist at Queen’s University until 1980 before moving to Edmonton to get her master of visual arts degree at the University of Alberta. While she was there, she met Miller, who was a film student from Vegreville, Alberta. They married in 1984. The couple discovered they had a common love of art as diverse as seventeenth-century Dutch high realists and the Dadaists, as well as a passion for popular culture, particularly classic black-and-white and sci-fi films. “We were seeing four movies a week then. Our favourites were Blade Runner, Don’t Look Now, and The Manchurian Candidate. We also read a lot of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “In he early eighties, they collaborated on a Super 8 film, and it was around then that George first wrote a script about a sci-fi character named Drogan, who would become a recurring figure in their work.”

Upon graduation, the couple moved to Toronto, where Miller enrolled in a multidisciplinary program at the Ontario College of Art, and Cardiff worked as a printmaker and lithographer whose work featured images from television, detective magazines, and film-noir movies. “I liked the medium,” says Cardiff, “because of the layering process that you could get. You take images from here and bring them there and mix them all together.” Still, life in a large city was less than satisfying. “We did bad art in Toronto,” says Miller. Cardiff elaborates, “There were too many influences, and a pressure to conform.” The couple moved to Alberta in 1987, where Cardiff took a teaching position at the University of Lethbridge, and later became an artist-in-residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts. There, with Miller’s help, she began adding another layer to her art: she developed soundtracks to accompany the presentation of her prints. Meanwhile, Miller, who’d been painting and considering a career in film, had begun making video installations.

One afternoon in 1991, Cardiff set out to explore a cemetery near the town’s outskirts. Rather than writing down her findings, she whispered her thoughts into a tape recorder. A short while along, she accidentally hit the machine’s rewind button. When she pressed play to get back to the point where she’d left off, she found herself walking in time with her own recorded footsteps, listening to the sound of her voice and the sounds around her, on tape. She calls it an “aha moment” – it led her to the innovation that is now a key characteristic of her work. “So much art happens serendipitously,” she observes.

Keen to explore the possibilities of her discovery, Cardiff began to play with the audio facilities at the Banff Centre, where she discovered binaural audio and portable digital audio sound. Using a dummy head, she mounted miniature microphones eighteen centimetres apart – the space between the average pair of human ears – to make various experimental recordings. When she played back her binaural tapes, she found they had a 3-D effect, allowing her voice to sound shockingly intimate and hyper-real, almost as though it were whispering inside a listener’s head.

Later that year, Cardiff created Forest Walk. Those who wanted to experience the piece were given a portable audio tape and headset, and a spot from which to start her tour. They’d press play to hear the artist’s voice guiding them outdoors and along Banff’s wooded trails, and end up experiencing a revolutionary work of contemporary art. In addition to conventional tour notes and sylvan sounds, the artist’s recording included a narrative about a confrontation with an elk. Her fictitious monologue was so startling that people left the walk feeling anxious and lost. Cardiff had figured out a way to jar her audience’s sense of reality, and she’d succeeded in taking the world of art outside the sheltered gallery space. Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, would later explain that Cardiff elaborated upon the twentieth-century form of the derive – a walk entirely dictated by chance. “Baudelaire’s idea of the flaneur [stroller], Paul Auster’s tramp, and Sophie Calle’s detective-like shadowing: these forms involve interaction with the street and relinquishment of control,” she noted. Cardiff added to the archetype by exploring the idea of the walker’s vulnerability.

[Graph Not Transcribed]

That same year, Miller created a media installation entitled Conversation/Interrogation. The viewer of the work sits in a chair as a man appears on the screen and begins a conversation with a person off-screen left. When the video cuts to this unseen person, it turns out it’s the viewer, who is being shot by surveillance camera. As the Canadian curator Scott Watson noted, “Miller’s work attempted something very similar [to Cardiff’s]. It involved the viewer in a performance of disembodiment.”

Cardiffs “walks,” as they became known, allowed her to break out onto the international stage. In 1996, the curator Kitty Scott got Cardiff into an exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark. Cardiff was soon asked to produce walks for the Skulptur: Projekte in Munster and the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. Miller worked on most of them, sometimes co-authoring, sometimes acting as her producer and managing the audio.

Each of the walks features the history, scenery, and sounds of its locale, as well as a fictitious narrative that plays on literary genres, such as the Gothic novel or the detective story, or on cinematic scenarios, all told in Cardiff’s voice. For example, the Whitechapel Art Gallery walk takes its listener from an East London library through the city’s streets. Against urban sounds, Cardiff injects a detective story that begins with the line, “The killer waited an hour….I’m wearing a red wig now; if he sees me, he’ll recognize me.” Fiction and the reality of the urban experience are conflated as Cardiff’s voice whispers, “Have you ever had the urge to disappear? Escape from your own life?”

The originality of the walks was Cardiff and Miller’s ticket to Venice. “Her work takes you on a tour,” says Marc Mayer of The Power Plant, “which is interesting, because a lot of museums take you on a tour. She’s taken a lot of her ideas from exhibitions and used them to curate the world around her.” Many curators approached the couple, asking if they could mount their work at the Biennale. (Under the application guidelines, a curator must present the artist’s proposal.)

Cardiff and Miller selected Baerwaldt, whose proposal eventually beat out twenty-one other contenders. He and his crew convinced this year’s jury – Mayer, Karen Love of Vancouver’s Presentation House, and Stephane Aquin of Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts – that not only would Cardiff and Miller create a compelling work of art, but Plug In could successfully produce and mount the exhibition, a daunting process that involves fundraising, promotion, transportation and installation, entertainment, and publishing a catalogue. It was a coup, considering the gallery has a staff of only six – and that the cost of putting on Cardiff and Miller’s piece is $750,000, three times that of the 1999 project, curated by the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Jessica Bradley.

Cardiff and Miller learned in late 1999 that they would represent Canada at the Venice Biennale. “When Wayne called us, we were, like, ‘Oh God, now we have to do the work,’ ” laughs Miller. The expectation was that they would do a walk. “People don’t realize how much pressure there is on artists to keep doing the same thing, to keep producing more and more of your signature style,” says Cardiff. But she and Miller had something different in mind.

The couple had just finished creating The Muriel Lake Incident, a sculptural tableau that featured an intricately detailed scale model of a cinema, where a film, made by them, played on a tiny monitor. They’d also begun work on Forty Part Motet, a project that came about after Cardiff hired a singer to help her with a recording for her White-chapel walk. “She recognized my interest in three-dimensional sound,” Cardiff explains, “and introduced me to the sixteenth- century composer Thomas Tallis’s Spem in Alium, one of history’s most intricate works of choral music. I was amazed to learn that it had forty separate harmonies, and right away I knew what I wanted to do.”

Cardiff arranged for England’s Salisbury Choir to perform the piece, each member wearing his or her own microphone. With the guidance of Miller, who mastered the sound system for the enormous audio work, Cardiff made an installation of the recording by placing forty speakers in the Rideau Chapel of Ottawa’s National Gallery, each one playing a separate part of the motet.

The idea was to have the audience walk through the chapel, around the speakers, and listen to the separate voices of the choir, as well as their recorded background noise – throat-clearing, coughing, whispers, the rustle of clothing. The result, which took them inside the experience of the music, was mesmerizing.

For The Paradise Institute, Cardiff and Miller drew upon elements from both Muriel Lake and Forty-Part Motet. “We had this idea of doing something that was even more enveloping,” says Cardiff, “but we weren’t sure what it would be.” The Paradise Institute marries sound and visuals, taking its viewers inside another medium: the experience of cinema.

The project began with Cardiff writing a script about Miller’s intergalactic character, Drogan. She and Miller spent over a year building the piece, writing, organizing video shoots, casting actors, and finding film locations. “We’d have long script discussions about what we could do, and where the piece should go,” says Miller. “It wasn’t until last October when we began the shooting that I realized we were going to have to work with professional cinematographers because I wasn’t happy with what we were getting.” Gradually, the work took form. When they saw a mysterious-looking, dark-haired actress in a trailer of a film done by a friend, they decided to create a part for her in the film. Then, Cardiff happened upon a picture of Volker Spengler, who’d starred in a few films by the German director R. W. Fassbinder. She knew he would have to star as best online casino the piece’s villain. “I faxed him and faxed him until he said yes,” she recalls.

Over twenty-five people worked on the piece, although Miller recalls that “it felt like five million were involved.” And the work continued until the opening night of the Biennale preview, when the artists were still tweaking The Paradise Institute, adjusting the sound levels of its audio component.

“I NEED THREE TICKETS,” AN IMpatient-looking man tells Noam Gonick, who stands in front of the Canadian pavilion, where he’s helping out Wayne Baerwaldt with crowd control.

“You’ll have to get in line there,” Gonick tells him, pointing at the horizon, “like, way down there. And it’s about a two-hour wait.”

It’s Friday, the third and final day of the Biennale’s preview, and a lineup of over 150 waits in the hot Venetian sun to get into the Canadian pavilion. There’s a level of frenzied anxiety among those who stand in line. This afternoon, the Biennale closes at 2 p.m. so that judges can begin selecting the winners, who will be announced the next day. There’s no guarantee that everyone waiting will be given a ticket and will have a chance to see what’s inside. Time might run out. Some are already frustrated. “Perhaps the artists should have given more thought to the limited number of people that their work could accommodate and considered whether their choice of what to make was appropriate for audiences [this] large,” remarks the internationally renowned art collector Ydessa Hendeles.

Among those in line, talk centres on highlights of this year’s exhibition. There’s the German artist Gregor Schneider, who’s recreated a distorted version of a tenement house from his hometown of Rheydt, featuring surprise spaces, claustrophobic corridors, and unusual passage-ways. There’s the American pavilion, where sculptor Robert Gober has made a version of flotsam – complete with cast-bronze “styrofoam” plates and a toilet plunger fashioned from terra cotta and hand-carved oak – to resemble the detritus that washes up on a beach.

The Canadian pavilion, which is shaped like a teepee, sits in a corner of Venice’s Giardini, sandwiched between the imposing stone structure belonging to the Germans and the elegant neo-classical temple-like showcase of the British. Small, and made of dark brick, Canada’s pavilion looks as if it was built by the Parks and Recreation department. It was in fact designed by a local architectural firm and offered to Canada by the Italian government in 1958 as a reparation payment after the Second World War. Sadly, it offers only a fraction of the exhibition space belonging to other national pavilions, and its unusual shape makes it a tough venue for an artist to place sculpture or hang paintings. “When I first phoned Janet and George, they didn’t know about the Canadian pavilion – what everyone freaks out about. I sent them photographs. They talled to video artist Stan Douglas, who told them that his art wouldn’t work there,” says Baerwaldt. “Anything that needs a certain kind of white cube space won’t sit well there. The pavilion can be a bit disconcerting unless you play with it.”

The element of play held appeal for Cardiff and Miller, who came to see the pavilion soon after learning that they would represent Canada. “They immediately seized upon an idea to make it work,” says Baerwaldt. “They saw that the pavilion was rather hidden by trees, and located off in a corner of the Giardini, but they liked its rather spooky possibilities.” “We’ve always been very interested in the funhouse idea,” explains Cardiff, “and in the idea of trying to create a ride.” Taking their cue from the carnival experience, the couple set out to build an artist’s entertainment that would offer provocation and escape to both those who knew a lot about art, and those who didn’t. Their pavilion would be an immersive environment, as riveting as the best rides at Disneyland. “Remember the Pirates of the Caribbean?” asks Miller, “It was an unbelievable design created by Walt Disney. He must have been on cocaine when he made it.”

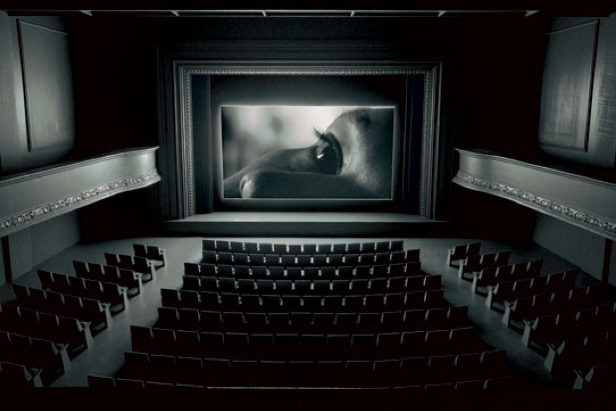

Outside the pavilion, Gonick, like a carnival attendant, rips out tickets from a coil that looks as though it came from a 1930s amusement park, and hands them out. “Entrez-vous,” he calls out to the happy group whose turn is next. One you’re inside the building, The Paradise Institute appears to be a tall plywood box, six-and-a-half metres by five metres by three metres, which you enter through a single door. Inside the structure, you immediately feel lush carpeting underfoot. From the doorway, look slightly to the left and there are two rows of luxurious redvelvet theatre seats, seventeen in all; look slightly to the right and you gaze over a balcony and onto the room’s lower level, packed with many more rows of seats – but miniaturized, each no larger than the size of a hand. There’s a sense that this space is part real, part imaginary. This is a film house that Lewis Carroll might have built.

The audience sink into their chairs. On the armrests are headsets that they’re instructed to put on. Lights switch off and a twelve-minute digital video begins. The story is set in the future, somewhere between the time of Chris Marker’s La Jetee and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. “We have general ideas of what the film is about,” says Cardiff, “but it’s not a linear narrative, there are gaps in the story, and there are scenes intentionally missed. There’s a relationship between the nurse character and her patient Drogan. But then there are also the bad guys.

They’re coming to do an experiment on Drogan. The nurse is trying to save him. It’s a simple story that we’ve heard many times.”

[Graph Not Transcribed]

What the audience has never heard before is an audio track like the one that accompanies this film. Against the dialogue of the movie’s characters, there’s the commotion of someone in the theatre chomping on popcorn and the ringing of a cell-phone. Then a voice whispers in your ear that she’s worried her stove was left on when she set out for the theatre. Upon turning to your neighbour, you see a person staring intently at the screen, and realize that the voice you heard was part of Cardiff and Miller’s piece. The eeriness intensifies when the footsteps of the film’s most sinister character go off-screen and reappear, somewhere very near you. Then he’s back on screen, staring you in the face, but he delivers his breathy lines just over your shoulder.

“During the piece,” Miller says, “some people turn around and tell the people behind them to shut up, only to discover that those people are on the tape. When we’re watching a film, it’s real to us. We wanted to play with that idea.” In the same way that Picasso and Braque used Cubism to explore the nature of the two-dimensional painted surface, Cardiff and Miller have set out to both investigate and break down the experience of cinema. “You go to the cinema,” says Cardiff, “and it’s not just about what’s on the screen. You walk into a movie theatre with memory: what someone said to you in line two minutes before. You sit down in a velvet chair and that affects your body, your sensuality. The cinema is a completely multidimensional, hyperlink experience.”

Audiences leave the Canadian pavilion with their hearts pounding. They’re unnerved, particularly by the ending of the piece – a house burns on screen against what sounds like the audience counting out loud, while, seemingly, outside the theatre, there’s the din of people pounding against the plywood. Is the lineup now clamouring to get in, or is the audience trying to escape the flames? Cardiff and Miller have literally put their viewers inside their art, but everyone has been forced to experience it individually. “You’re in a theatre,” says the Berlin-based artist Laura Kikauka, “but it’s more like a little hideaway. You’re wearing headphones, so you’re not talking to your neighbours, and people aren’t watching you the way they might in a gallery. You’re in isolation, and the experience is an entirely personal one.” The world’s art elite have stepped up to Canada for a ride and have left not knowing exactly where they are.

BY 7 P.M. ON SATURDAY, THE delirious pace that has gripped the Canadian pavilion for the last three days has grown slack. Showings of The Paradise Institute have stopped and everyone involved in its production, including Cardiff and Miller, has moved to the small adjacent garden, which looks out on the sea. A cool evening wind rustles though the leafy trees; Proseco is flowing again. The mood is equal parts triumph and exhaustion. When the Biennale judges announced the year’s winners – Cardiff and Miller – two hours earlier, an anticlimactic mood had already set in. On Friday, the three-day preview ended and the Giardini remained shut for almost a full day as the international jury deliberated over its decisions. Most of the art world was absent from the ceremony, having returned home for the weekend already aware of who the stars of this year’s Biennale have been. The awards ceremony itself, which took place in a massive white tent set up in the heart of the Giardini, offered little of the glamour and flash that characterized the previous days’ events. Like students at a university graduation ceremony, Cardiff and Miller heard their names called out as winners, stepped up to the podium, shook hands with the jurors, and returned to their seats with their prize, a conventional-looking square plaque inscribed with their names beneath a golden symbol of Venice, the lion of San Marco.

In the pavilion garden the buzz is about accolades much larger than trophies. Tales are being recounted of the leading figures who have been through The Paradise Institute. The rumour is that New York’s Museum of Modern Art will buy the work, and that the Art Institute of Chicago is going to commission Cardiff and Miller to do a new installation. As the director of the show that took this year’s Biennale by storm, Baerwaldt has also been noticed. “Winning at Venice puts a curator’s career over the top,” remarked Mayer before the preview opened. Today, the Plug In director is receiving invitations to curate shows internationally, and there are murmurs that he may be invited back as a judge at the 2003 Biennale.

When the Giardini shuts down at dusk, there is no Canadian party to attend – at least not one that’s on the scale of the opening-night gala. It is as though Baerwaldt and his skilled team, who so carefully planned every detail of Canada’s presentation, did not dare to tempt fate and imagine just how spectacularly their year-long efforts might end. The crowd breaks up into small parties, which head off for dinner still bewildered about what they’ve pulled off. Later in the night, the groups reconvene at the Venetian nightclub Piccolo Mondo. Its name translates as “small world” but it is more like another sort of paradise institute, where revellers drink and dance until daybreak. Cardiff and Miller aren’t here, though. They’re enjoying a quiet meal with other prize-winners and the jury. They’re gratified by the award, but even more so by the reception they’ve enjoyed with audiences. “The Paradise Institute got inside all our psyches,” Cardiff observes. Says Miller, “The experiment worked.”

Against the film’s dialogue, you bear someone chomping popcorn, a cellphone ringing. Someone whispers in your ear she’s worried she kept the stove on when she left for the theatre. You turn, but your neighbour is intently watching the screen The pavilion is tucked away, hidden by trees. The artists liked its spooky feel. “We’ve always been interested in creating a ride,” says Cardiff. “Remember the Pirates of the Caribbean at Disneyland?” asks Miller. “It was unbelievable”