Paintings that have been restituted to the Max Stern estate, including The Girl from the Sabine Mountains, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter. The works are to be part of the Stern exhibition – if it happens. (Christinne Muschi/Reuters)

Backlash as Max Stern exhibit dubbed ‘Too Canadian’ for Dusseldorf

A German mayor’s meddling in a landmark show on Max Stern’s Nazi art loss has a new focus: downplaying its Montreal roots

—

In the late days of 2017, the German city of Dusseldorf became the unlikely centre of a scandal that outraged art circles and the international Jewish community. Dusseldorf mayor Thomas Geisel cancelled an exhibition honouring the Canadian art dealer Max Stern, who before immigrating to Montreal was forced by the Gestapo to sell over 200 paintings at a 1937 auction. Today, the Max Stern Restitution Project, founded in Stern’s name and based at Concordia University, is one of the world’s most influential organizations dedicated to reclaiming Nazi-looted art.

The exhibition “Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal,” was to open at his city’s Stadtmuseum before travelling to Haifa’s Museum of Art and Montreal’s McCord Museum this year—until Geisel pulled the plug on the show last November. He then flip-flopped on his decision on Dec. 21 following an outpouring of international outrage, including pressure from Germany’s culture minister Monika Grütters, who called the mayor’s actions “beyond regrettable” adding that exhibitions exposing Nazi wrongs “are more necessary than ever at the current time.” Dusseldorf’s cultural office then gave official word that the show would be revived.

However, recent events suggest that the real story, in which Canada plays a key role, is still unfolding. Despite Geisel’s recent promise to reinstate “Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal,” he has yet to fix a date for the show. Moreover, if the exhibition does go forward the mayor has been clear that it will be in a different format from its original, which he says was “too Canadian.”

If the Canadian art cognoscenti are unimpressed with that explanation, they’re not the only ones. According to Willi Korte, the Bavarian-born Washington-based lawyer, historian, and restitution expert, “this is an elaborate stall tactic” that allows a politician to save face in a city deeply divided on the subject of returning Nazi-looted art to its original owners.

Geisel’s initial reason for cancelling the exhibition was that it could not take place because the Stern estate has claims against Dusseldorf public institutions, which it maintains has paintings that Stern had to give up under Gestapo orders. While Geisel seemed to soften his stance in the wake of the backlash, he has made no efforts to work with Canadians to ensure that the show is realized.

In late January the mayor visited Washington, D.C. and then New York City to make amends with his most vehement detractors, including Georgetown University professor Dr. Ori Z. Soltes and Manhattan’s Holocaust Claims Processing Office. Oddly, the mayor’s North American tour did not include a trip to Montreal, the home of the Max Stern Restitution Project, where he could have met with its key stakeholders.

The bypassing of Canada is raising eyebrows about the mayor’s promise to realize an exhibition that has been in the works for more than three years. Unless Geisel cooperates with Stern’s representatives, Stoltes mused in an interview after his meeting with the mayor last month, “How will this new reinstated exhibition come about?”

The genesis of “Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal” was the Stadtmuseum’s April 2014 return of Self-Portrait of the Artist by the 19th-century artist Wilhelm von Schadow. The painting was one of more than 200 paintings, inventory Stern sold involuntarily from his Rhine Valley dealership, the Galerie Stern. Under Gestapo order in 1937 he was forced to auction off the works from his family business at depressed prices after Nazi law revoked his professional credentials as an art dealer because he was Jewish.

In 2011, when Stern’s heirs located Self-Portrait of the Artist at the Stadtmuseum, the museum’s director, Susanne Anna was unaware of the work’s problematic history. She then committed herself to ensuring the painting’s restitution and announced to the international press that her museum would organize an exhibition about how the Galerie Stern had once been a vibrant component of German cultural life before it was erased from history along with countless other Jewish establishments.

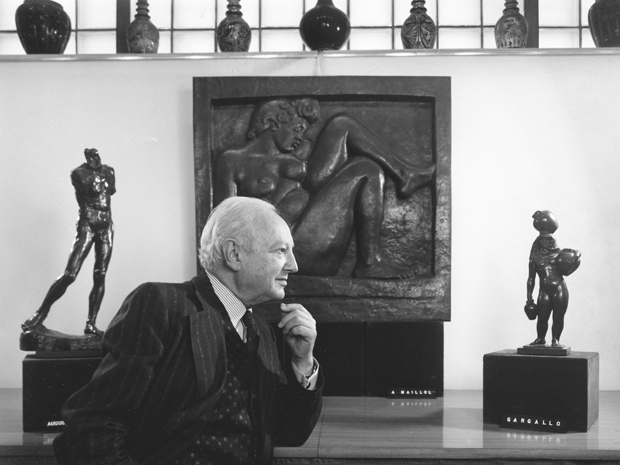

Max Stern.

JEWISH SENIORS ALLIANCE

For three years Anna planned the exhibition’s curatorial direction in concert with the world’s leading Stern experts, the National Gallery of Canada archivist Philip Dombowsky (who oversees Stern’s papers) and Catherine Mackenzie, who curated an exhibition on Stern in 2006.

She also involved Geisel in the exhibition from the start. Marnie Stein, the principal of a Jewish grade school in Côte Saint-Luc told Maclean’s how in 2015, the mayor had visited Les Écoles juives populaires et Les Écoles Peretz, along with Susanne Anna to establish a partnership between the school and the Max Schule, an elementary school in Dusseldorf. As a pedagogical component of the exhibition, two grade three classes—one in Dusseldorf, the other in Montreal—would do twin studies on Max Stern and what his life meant to both their respective countries.

“When Geisel visited the school he came across as likeable, engaging and committed to the issue,” said Stein, “The meaning of his visit was not lost on the students, many of whom are offspring of Holocaust survivors.” They presented him with a Habs jersey with his name on the back. Students felt hopeful and excited about the plan for the two schools to collectively create art and research that would be featured in the travelling Stern exhibition. It was a model, said Stein, for how “despite great historical adversity, in remembering the past they could collectively forge a better path in the future.”

Stein says she finds it “deeply troubling” that she has received no communication about what is happening with the exhibition. Students want to know, “Are we out of the picture?”

Equally worrying for some is that the curatorial vision for the promised exhibition is itself now under scrutiny. Last week, Dusseldorf’s Cultural Affairs Officer Hans-Georg Lohe announced that the 78-year-old renowned art historian Uwe Schneede will be involved in an unspecified role on the “initially canceled Max Stern exhibition.” In a phone interview, Geisel explained the show had to be “modified” with new additions to the curatorial team—“for balance,” because the exhibition’s initial conceptualization did not have enough German representation.

However, the reason Anna looked outside of Dusseldorf in creating the exhibition in the first place is precisely because there are no leading scholars on Stern in Germany. After being forced to flee his home country, Stern took his possessions and papers to Montreal, which became an important centre for study on him and his work.

Anna, Dombowsky, and Mackenzie created a show to focus on Stern’s life in Germany, where he ran one of the country’s most successful galleries, as well as Montreal, where he rebuilt his life and became director of the Dominion Gallery of Fine Art, selling contemporary Canadian painters at a time when it was more fashionable to collect European artists. Despite Stern’s success and fame in Canada he never shared details of the losses he incurred in Nazi Europe. Following his death, in 1987, Stern’s executors—Montreal’s Concordia and McGill Universities and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem—learned of his past and established the Max Stern Art Restitution Project. To date the organization has reclaimed 16 paintings, working at a rate of approximately one recovery per year since it was launched in 2002.

The Max Stern Art Restitution Project has also become one of the world’s most important voices in the study of Holocaust-era art looting, setting precedents such as its 2008 restitution of The Girl from the Sabine Mountains, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, which was the subject of a landmark U.S. legal case, in which U.S. District Chief Judge Mary Lisi ruled “Dr. Stern’s relinquishment of his property was anything but voluntary.” The decision was historic, because it recognized that the majority of European Jews lost their artworks through Nazi coercion, acknowledging for the first time that this forcible selling of art was tantamount to theft.

Like Stein, the original curatorial team for the exhibition has received no information about the show’s new manifestation, its scope and vision, or whether they will be involved in it. By email, Mackenzie wrote that she still hopes to play a part in “bringing the story of the Stern family’s presence in various art worlds to the attention of an audience in Germany.” However, as she explained, “there has been no approval from Dusseldorf’s cultural department of funding for the revived project.”

As for Canadian-based funding for the exhibition, this, too, is a potential challenge. A key sponsor of the show was to have been Montreal’s Jewish Community Foundation (JCF). Its support, however, was predicated on the plan to take the exhibition to Montreal’s McCord Museum. “Since the show was cancelled and then re-announced, we haven’t heard anything,” says Robert Kleinman, executive vice-president of the JCF. Until the JCF has more information on the revised exhibition plan and its confirmed venues, he says, “no funds are forthcoming.”

In an interview, Suzanne Sauvage, McCord’s president and chief executive officer said that although she is hopeful that the show will arrive in Canada, its status is “tentative, because Dusseldorf is looking for new curators and it will have to find new financing.” In order for the show to happen in 2018 or 2019, these things should be in place by now. “Shows are organized years in advance,”

Art world watchers are starting to ask how it is that that Geisel can make promises to hold this politically freighted exhibition, which now seems unlikely to be delivered as it was originally intended. Not to mention how a mayor in any democratic country can hold this much power.

One answer lies in the comments that Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, gave on Feb. 1 in Berlin on the current state of art restitution in Germany. “The huge gap between official announcements and actual deeds must end,” said Lauder. He added that there will be no justice until, the federal government of Germany takes responsibility and makes restitution “a top priority at the state and municipal levels.” Geisel was in the audience at Lauder’s talk. But he has yet to offer any further insights about Dusseldorf’s plans for the Stern exhibition, leaving its future still very much in question.

Yet the topic is one that the mayor can’t ignore. Last week the heirs of Kurt Grawi, who fled Germany under Nazi persecution, made a claim on the painting Füchse by the Expressionist master Franz Marc, one of the key works in Dusseldorf’s Kunstpalast. (It’s valued at up to 14 million euros.) With Nazi-looted art remaining an issue that is tied to his city, Geisel is under more scrutiny than ever.