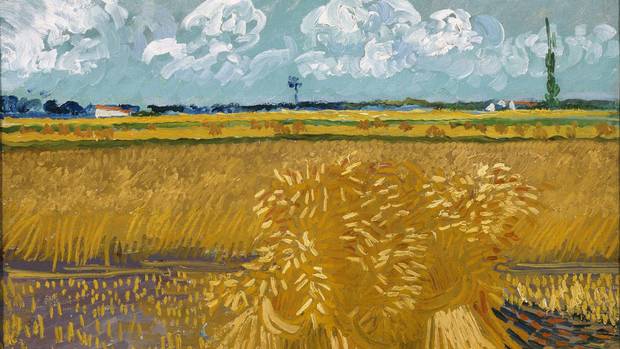

Detail from Vincent van Gogh”s Wheat Field with Sheaves (1888; oil on canvas)

At Ottawa Exhibition, You'll See Another van Gogh

We associate him with sunflowers, swirling bold brushwork, starry nights, the colour yellow and the details of an incomparably dramatic life. After dabbling in a number of professions, Vincent van Gogh became an artist at age 27. He painted so prodigiously that it took him only a decade to lay a foundation for 20th century art. But plagued by mental illness, he was driven to acts of despair. In 1888, while at a brothel, he sliced off a portion of his left ear, wrapped it in a newspaper, and asked a prostitute to “keep this object carefully.” Less than two years later, he was dead from a self inflicted gunshot wound to the chest.

Such details have led to biographically rooted interpretations of the artist in which his madness and highly intense style upstage his method. Now, thanks to the National Gallery of Canada’s groundbreaking exhibition Van Gogh: Up Close, which opens Friday and runs until September, the world will have an important new way to see the 19th century genius. When it came to creating the structure of his paintings, van Gogh was not only highly deliberate and rational, he was influenced by the most popular and ubiquitous new medium of his day: photography.

Co curated by the internationally renowned van Gogh scholar Cornelia Homburg and Anabelle Kienle, assistant curator of European and American art at the National Gallery of Canada, Up Close showcases 40 mid to late career paintings by van Gogh that feature an incredibly inventive use of camera like crops, or close ups, on elements in nature – including plants, trees, flowers and insects. “It’s always been said that van Gogh wanted nothing to do with photography,” Homburg says. “In this show we demonstrate that that view has to be modified.”

Born in 1853, van Gogh grew up in the Dutch province of North Brabant, the eldest son of a Calvinist clergyman who taught his children to lead a pious life. His first significant interaction with photography was at age 16, when he moved to the Hague to work for the publishing company Goupil & Cie. He wrote his brother Theo that the firm produced books as well as individual photo reproductions “of all genres … from Italy, Switzerland, Spain, studies of landscape, architecture, and figure, etc.” One of van Gogh’s key responsibilities at Goupil was to grow its holding of fine art reproductions, which allowed him to assemble his own photography collection of works by old masters and contemporary painters.

By the time van Gogh became an artist in 1880, he was interacting with a wide range of photographic material. Not only did he keep images clipped from popular periodicals including The Illustrated London News and Harper’s Weekly, he had photographs made (by Petrus Henricus van Bemmel) of two 1884 paintings, The Sower and Woman Spinning, items included in the exhibition and the only surviving evidence of the original works.

Arguably, the most important camera related influence on van Gogh were photographic catalogues of source and reference material for artists – including flowers, landscape formations, tree trunks and forest growth. Such volumes, popular as memory aids among 19th century painters, included camera made images of natural details, often isolated against a neutral or abstract background.

The roots of the Ottawa exhibition stretch back to 2006, when Homburg mentioned to Kienle (who had worked as her intern at the Saint Louis Art Museum) that the National Gallery of Canada had one of the finest examples of a van Gogh “closeup”: Iris, a work he executed in the garden of the SaintRémy asylum, where he voluntarily admitted himself in May, 1889.

Before long, the National Gallery asked Homburg to collaborate on originating an exhibition based on how van Gogh pushed the boundaries of closeup views of nature more than any other painter before 1890. It’s the first exhibition on the painter’s work to be shown in Canada in 25 years and stands out because it features domestically originated new research on one of history’s most studied artists; as Homburg puts it, “One thinks, What new can there be?”

In addition to photography, the exhibition reveals there were other important sources for van Gogh’s unique framing of nature. Like other late 19th century European artists, he was captivated by Japanese woodblock prints, whose compositional freedom, unconventional use of perspective and off centre placement of subject matter freed painters from conventional ideals of Western art academies.

Despite the camera’s influence on van Gogh, he had an ambivalent, even dismissive relationship with photography. Unlike his contemporaries Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillet, all of whom enthusiastically embraced the medium, van Gogh disliked photography’s colourlessness and complained how posed studio portraits “always [had]the same conventional eyes, noses, mouths, waxy and smooth, and cold.”

In part, van Gogh’s trademark vibrant palette can be understood as a rebellion against black and white photography. In 1888, he painted a picture of his deceased mother, Anna Cornelia, based on a photo taken eight years earlier to imbue it with hues that the camera did not offer. For van Gogh portraits came to life from deep in the soul of the painter, a place, he wrote, “where the machine can’t go.”