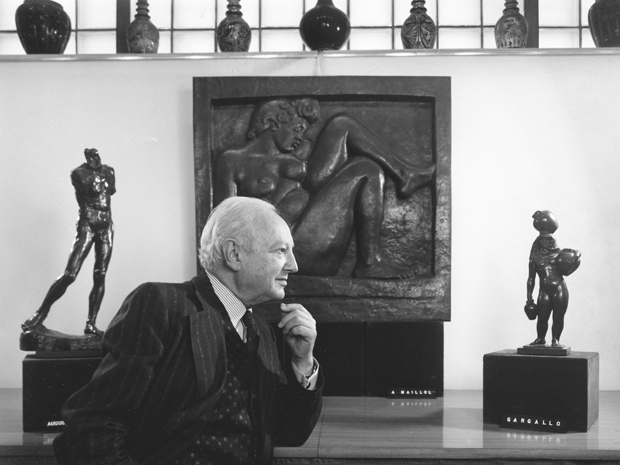

Lauder.

WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS

Ronald Lauder Takes Germany To Task Over Lack of Action on Art Restitution

Fate of Düsseldorf exhibition on Jewish art dealer Max Stern, still without a start date, appears to be mired in local politics

—

Last night Ronald Lauder, the American businessman, art collector, and president of the World Jewish Congress, demanded that Germany do more to address Nazi-era art theft, a subject that, 73 years after the end of World War II, is still far from being resolved.

At the Axel Springer Journalists Club in Berlin, Lauder hosted an event to mark the beginning of the 20th-anniversary year of the Washington Declaration. In signing the 1998 pact, Germany, along with 43 other nations and 13 nongovernmental organizations, voluntarily committed itself to the recovery of art stolen by the Nazis or forcibly sold under Third Reich duress.

Lauder was direct in his criticism of the current state of restitution in Germany. He preceded his remarks by saying, “I may not be welcome here after what I say, but I think it is best to be completely honest with all of you.”

“The fact that we are still dealing with this topic is simply not acceptable,” said Lauder. “If Nazi-Germany had not stolen so much Jewish owned art in the first place, we would all be doing something else tonight.”

He pushed for action, remarking that “Germany has promised much, but has, so far, done the bare minimum to solve this problem.”

Max Stern in Germany around 1925.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

AN EXHIBITION CANCELED, THEN ABRUPTLY REINSTATED

In last night’s audience was Düsseldorf mayor Thomas Geisel whose recent controversial actions Lauder alluded to with his remark that among those to blame are “local politicians who cancel long-planned exhibitions for either political gains or other reasons.”

One of 2017’s most disturbing art world events happened last November, when Geisel abruptly canceled “Max Stern: From Düsseldorf to Montreal,” an exhibition about the life of one of the city’s renowned Jewish art dealers and his persecution by the Gestapo, who forced him to sell more than 200 paintings in 1937. Among his reasons for terminating the show, which was to have opened this week at the city’s Stadtmuseum, Geisel cited claims against the city by Max Stern’s estate.

On December 21, just one month later, Geisel did an about-face following an outpouring of international anger. He announced that the exhibition was back on in Düsseldorf, and that it would travel to Haifa, Israel, as originally planned, and then on to the McCord Museum in Montreal (where Stern settled after he fled Düsseldorf) in 2019.

In the wake of the cancellation, Geisel’s most influential and effective critic has arguably been Lauder, who in a statement released by the World Jewish Congress on November 29, remarked, “Considering the fact that the current German government has made tremendous progress in regard to provenance research, canceling this exhibit would be a major setback, especially for the victims of the Holocaust and their heirs.”

On the same day that Lauder made this comment, Hagen Philipp Wolf, speaking on behalf of the German culture minister, Monika Grütters, condemned Düsseldorf’s termination of the Stern exhibition, calling the decision “beyond regrettable” and adding that “exhibitions aimed at confronting Nazi wrongs are more necessary than ever at the current time.”

One of the exhibitions Grütters was referring to was “Nazi Art Theft and Its Consequences,” which opened on November 3 in Düsseldorf’s neighboring city, Bonn, to spotlight the 2013 discovery of more than 1,500 works—many owned by persecuted Jews—hidden for decades by Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a Nazi art dealer. Grütters described the Gurlitt show as a manifestation of her commitment to “how important research into this bitter chapter of Nazi policy remains.”

NO FIXED DATE

While the Stern exhibition has been reinstated, questions remain about whether it will ever come to fruition. On Tuesday, Mayor Geisel told ARTnews by phone that a fixed date for the show is yet to be determined. In addition to Geisel’s reluctance to state the show’s exact time (though “a tentative date of November 29, 2018” has been given for a symposium on Stern, to take place at the Stadtmuseum), he explained that the vision for the exhibition will be “modified” and it will involve a new, yet-unnamed curator.

According to Dr. Willi Korte, the Bavarian-born, Washington-based lawyer, historian, and internationally renowned restitution and provenance expert, Geisel’s announcement that he was reinstating the exhibition may likely be “a fig leaf,” one that was put in place as a political maneuver to “stop all the bleeding following the cancellation.”

Lauder has a more diplomatic view. He told ARTnews by email Wednesday, prior to his Journalists Club speech in Berlin, “I welcome the Mayor’s decision to reopen the Max Stern exhibition. Now, it will be of fundamental importance that the city of Düsseldorf design a concept that convinces the international partners in Canada and Israel to reengage—as was the case with the original plans.”

Wilhelm von Schadow’s Self Portrait of the Artist, 1805.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A PAINTING RESTITUTED

The genesis of “Max Stern: From Düsseldorf to Montreal” was the Stadtmuseum’s April 2014 restitution of Self-Portrait of the Artist by the 19th-century Romantic painter Friedrich Wilhelm von Schadow. An early director of the Düsseldorf Academy, von Schadow shaped one of Europe’s most famous art schools, the alma mater of Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, and Andreas Gursky.

The Stern estate located the painting in the catalogue for “The Hudson on the Rhine,” a 1976 exhibition at the Dusseldorf Kunstmuseum of mid-19th-century American artists who had attended von Schadow’s academy. The estate tracked down the painting at the Stadtmuseum, which was unaware of the work’s tainted provenance.

Self-Portrait of the Artist was among the paintings that Stern put up for sale on November 13, 1937, after Nazi law deemed him incapable of promoting German culture because he was Jewish. Faced with no other option, Stern liquidated the inventory of his family’s well-regarded Rhine Valley art dealership, the Galerie Stern. He listed the items at depressed prices in sale No. 392 at Cologne’s Third Reich–approved auction house Lempertz—infamous for trafficking “non-Aryan property” and where Cornelius Gurlitt sold a work by Max Beckmann in 2011.

After escaping Germany, Stern settled first in London, then in Montreal, where he rebuilt his life and became director of the Dominion Gallery of Fine Art. Stern never saw a penny from the Lempertz sale; its proceeds were ransomed by the Nazis to obtain his mother’s exit visa to leave Germany.

After Stern’s death in 1987, his heirs, and Montreal’s Concordia and McGill Universities, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, learned of the dealer’s losses during the Nazi era, including the art that he sold under duress in 1937—facts that Stern had never discussed during his lifetime. (Having no family, Stern left his estate to three universities.)

To break Stern’s silence, his executors established the Max Stern Art Restitution Project “to meaningfully address his losses,” said Clarence Epstein, the organization’s director. Today, the initiative is one of the world’s most notable programs investigating Holocaust-era cultural theft. Since three universities run the project, all proceeds from the sale of any restituted works go back to the organization. “We are a perpetual plaintiff,” said Epstein. “Our goal is to put Max Stern back into the cultural narrative by reclaiming his art, no matter what its current market value is, to further the study of Nazi-era art restitution.”

Epstein’s message resonated with Dr. Susanne Anna, director at the Stadtmuseum. At the restitution ceremony for von Schadow’s Self-Portrait of the Artist in 2014, she stated before an auditorium packed with international media that her museum would organize an exhibition examining the place of Stern and his gallery in Düsseldorf’s cultural life before the Nazis erased the names of Jewish art dealers from the city’s history.

Thomas Geisel, the mayor of Düsseldorf.

OB_THOMASGEISEL/TWITTER

CURATOR TO BE ADDED ‘FOR BALANCE’

To put together the exhibition, Anna recruited the world’s leading Stern experts: the National Gallery of Canada archivist Philip Dombowsky (who manages all of Stern’s papers, including those he took with him while escaping Germany) and Montreal professor Dr. Catherine Mackenzie, who curated an exhibition on the 1937 Lempertz sale in which Stern liquidated his assets. Dr. Anna worked on the show for three years, forging partnerships with Haifa’s Museum of Art and Montreal’s McCord Museum, the venues for the exhibition following Düsseldorf.

Although Mayor Geisel has committed to reinstating the Stern exhibition, its vision and mandate will differ from what Dr. Anna had planned. In the days following Geisel’s cancellation of the exhibition he explained that its curatorial focus was not “balanced enough” because of its heavy reliance on Canadian scholarship.

Geisel told ARTnews that “one or two more [curatorial] personalities” need to be added to the exhibition team “for balance.” Yet there are no leading scholars on Stern in Germany, the country he was forced to flee. Stern took his life, possessions, and papers to Canada, which became a stronghold for study on him. Until Geisel announces the show’s new curatorial additions, its scope and vision remain unresolved.

If, as Lauder points out, a key component of ensuring the exhibition’s success lies in convincing Düsseldorf’s international partners to reengage, the likelihood of the exhibition taking place at all is low. The Stadtmuseum has contacted neither Dombowsky nor Mackenzie as to what role, if any, they might play in the newly conceived exhibition.

“I am still hoping to be instrumental in bringing the story of the Stern family in various art worlds to the attention of an audience in Germany that would, I believe, find it fascinating,” Mackenzie said. She added, however, that “there has not been confirmation from [Düsseldorf’s] cultural department of funding for the revived project, funding for the earlier success of which was fractured by the cancellation. It is [also] unclear what the relationship is intended to be between the symposium and the reinstated exhibition.”

DÜSSELDORF MAYOR MET WITH CRITICS DURING U.S. VISIT

Last Thursday and Friday Mayor Geisel visited North America. His itinerary included New York and Washington, D.C., where he met with his most outspoken critics, including Georgetown University professor and lecturer in theology and fine arts Dr. Ori Z. Soltes and Marc Masurovsky, co-founder of the Washington-based Holocaust Art Restitution Project. Conspicuously absent from the mayor’s trip was a stop in Montreal. “This leaves a lot of unanswered questions,” said Soltes. “While Geisel may have many strong intentions to see the exhibition happen, there are key details that need to be filled in before this can happen, including how he will work with the Max Stern Restitution Project.”

Epstein told ARTnews he will comment on this subject once he receives a report from Düsseldorf as to how the reinstated exhibition will unfold. “As with any international exhibition that has been publicly announced, by now there should be concrete information about its proposed timing, scope, funding, organization, catalogue, and curators,” he said. “Yet on all of these matters, we await information and answers.” In the meantime, the Restitution Project continues to focus on its core mission: recovering paintings that were stolen from Stern.

Max Stern.

JEWISH SENIORS ALLIANCE

This controversy is the central one when it comes to whether or not the Stern exhibition will happen. “It all comes down to the fact that while there are many Germans who want to do what is morally correct and return Nazi-looted art,” said Epstein, “according to the country’s civil law, property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it was lost or stolen.” Nazi-era art restitution in Germany has been particularly challenging since the door to reclaiming works through German courts shut in 1975.

“Keep in mind that Geisel first said he canceled the exhibition because Max Stern’s estate has claims against the city of Düsseldorf,” said Epstein. “Claims that the city rejects.” Lauder noted in his November 29 statement that it was absurd that the city’s officials justified their cancellation of the exhibition “because victims of Nazi art loot[ing] and their heirs are still looking for their property.”

If Korte is correct in his characterization of the reinstatement of the exhibition as a “fig leaf,” it is likely that the show’s planning is being dragged out intentionally. This would allow the Stern exhibition to serve as a smoke screen for Geisel, something he can use so as to appear sympathetic toward recovering art stolen during the Nazi era while holding power in a city “that has deep ties to German industry,” said Korte, “and a record of being unsympathetic toward restitution claims.” (Geisel is expected to seek reelection in 2020.)

As Lauder made clear in his address last night, while the Washington Declaration was a historical landmark, the pact has never been legally binding. When it comes to addressing restitution in Germany, he said, “the huge gap between official announcements and actual deeds must end.”

It remains to be seen whether Lauder’s most recent criticisms will have an effect in Düsseldorf. “Lauder’s words already once significantly affected Geisel’s thinking,” said Epstein. “Hopefully, his comments last night will make a renewed impact on the mayor.”