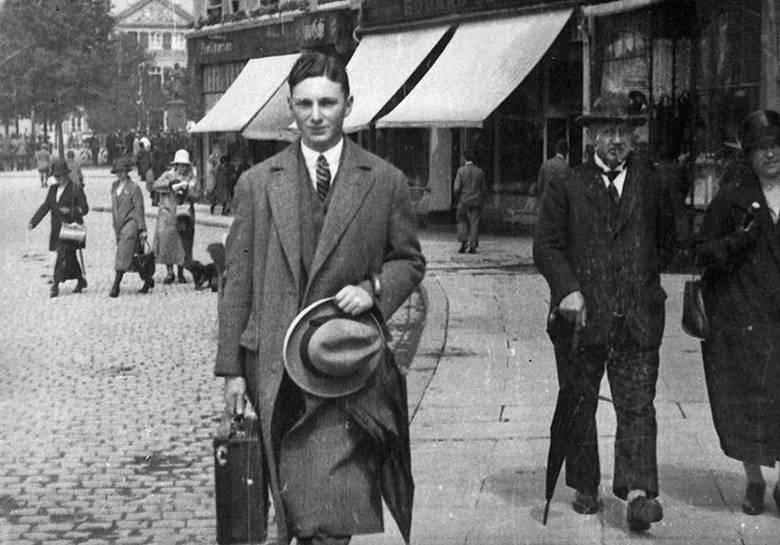

Max Stern rebuilt his life in Canada after anti-Semitic persecution forced him to leave his native Germany.

KARSH

Restoration drama

An art-world scandal is brewing over Dusseldorf's abrupt cancellation of a show about noted Montreal dealer Max

Stern, whose earlier collection the Nazis forced him to sell,

Sara Angel reports.

—

International outrage has erupted over the abrupt termination by the mayor of Dusseldorf, Germany, of a museum exhibition called Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal, about the famed Jewish art dealer Max Stern and the restitution of paintings that the Nazi Gestapo forced him to sell in 1937.

The premise of the show, which was set to open in February at the city-owned Dusseldorf Stadtmuseum, was to teach the story of Stern, who rebuilt his life in Canada after anti-Semitic persecution forced him to leave his native Germany, and how his heirs created the Montreal-based Max Stern Art Restitution Project, now one of the world's most significant initiatives addressing Holocaust-era cultural theft.

Under Mayor Thomas Geisel, the city issued a statement explaining its reason for pulling the plug on the landmark show as "restitution claims in connection to Max Stern" – whose stolen art still hangs on public gallery walls in Dusseldorf. But it neglected to mention the city's ties to the Berlin-based lawyer Ludwig vonPufendorf, one of Germany's most outspoken and vehement critics of Nazi-era art restitution. The cancellation of the Stadtmuseum show is particularly questionable as it comes at the same time that, in nearby Bonn, the Bundeskunsthalle museum opened an exhibition on the Nazi-tainted hoard of Cornelius Gurlitt, to raise awareness of Second World War crimes committed by the country. Collectively, the situation underlines the challenging nature of art restitution and Germany's divided and inconsistent handling of the matter.

"Ownership claims should be a goal and incentive, not a hindrance, to this important exhibition," Tel Aviv University professor emerita Hanna Scolnicov says. "Human lives cannot be returned, but art works can and should." In a letter to the mayor, Georgetown University professor Ori Z. Soltes wrote that where a respected German museum had the opportunity to "heal wounds that remain open more than seven decades after they were inflicted," it instead "unilaterally cancelled the project" to protect illegitimate holdings. Contacted for his comments about the cancellation, Geisel has not responded.

In development for three years, Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal was to open at the Stadtmuseum before travelling to the Haifa Museum of Art in Israel and then to Montreal's McCord Museum. All components of the show had been completed when, earlier this month (only days before the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the wave of anti-Semitic violence throughout Germany in November, 1938), Dr. Susanne Anna, its curator and the Stadtmuseum's director, received written notice from the city of the cancellation.

"This sort of behaviour is highly unusual in the museum world," says Suzanne Sauvage, McCord's president and chief executive officer. "Loan agreements for works of art had been negotiated and signed, support activities had been planned, funds had been raised. All was set to go." (The exhibition will not take place in Montreal or Haifa because it was dependent on holdings of the Stadtmuseum and the work of its curators, who initiated it.)

Cover of 1937 Lempertz catalogue of Auction 392.

MAX AND IRIS STERN FOUNDATION

Named for the renowned Montreal art dealer who played a key role in the careers of Canadian painters including Emily Carr and Paul-Émile Borduas, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project was founded in 2002 after Stern's heirs – McGill University, Concordia University and Israel's Hebrew University – learned that before Stern's arrival in Quebec, Third Reich legislation brought an end to his esteemed Rhine Valley art dealership, the Galerie Stern in Dusseldorf.

When Nazi law deemed Stern incapable of promoting German culture because he was Jewish, he involuntarily liquidated the inventory of his family's art business, in sale No. 392 at Cologne's Third Reich-approved auction house Lempertz (still open for business today), infamous for trafficking "non-Aryan property" to Hermann Goering, Adolf Hitler's deputy and most avaricious looter. The Max Stern Art Restitution Project was established to reclaim the works lost at that 1937 auction.

Despite successfully reinventing himself in Canada, where he ultimately received the Order of Canada for promoting living Canadian artists at his Dominion Gallery in Montreal, Stern, who died in 1987, never discussed the losses he incurred in Nazi Europe.

It was to break this silence that his executors created the Max Stern Art Restitution Project (to date, 16 works have been restituted). It is a not-for-profit organization that has no time limit, nor monetary incentives when reclaiming art other than to further the understanding of restitution.

"It is the only operation of its kind in the world," explains its director, Dr. Clarence Epstein of Concordia. "Because we recover art that ranges in value, including pieces worth little on today's market, our work counters a notion often fed by media that money rather than moral rectitude is at the heart of Holocaust-era art restitution."

Exterior of the Galerie Stern in Dusseldorf, 1935.

MAX STERN FONDS, NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES

The Dusseldorf Stadtmuseum announced its plans for an exhibition about Max Stern in April, 2014, at a restitution ceremony in the gallery, where it returned to the Stern estate the painting Self-Portrait of the Artist by the 19th-century Romantic artist Wilhelm von Schadow. Five years earlier, in 2009, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project had discovered the work in the inventory of the museum. The painting had been listed as one of the items in the 1937 catalogue for the forced auction at Lempertz.

At the ceremony at the Stadtmuseumwhere the painting was returned to Stern's estate, Susanne Anna announced that under her direction the museum would organize an exhibition to acknowledge the Galerie Stern's importance to the city of Dusseldorf, because the Third Reich had erased its history, as well as the stories of the city's other Jewish art dealers. She explained the show was necessary as a reminder that "art was only one thing stolen by the Nazis. They took everything – rugs, bicycles, cars, carpets, candlesticks and books – turning Germany into a garage sale of Jewish goods to finance the war."

What Anna left out of her speech, however, was the highly arduous process that the Stern heirs had faced in reclaiming Self-Portrait of the Artist, one that took five years in a city known for its conservative values.

"It was complicated," Epstein says, "because Germany has no set laws outlining how to deal with claims." Moreover, the country's civil code states that property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it was lost or stolen. Thus, the door to restituting works through German courts was shut in 1975. While Germany is among 44 countries that voluntarily signed the Washington Principles of 1998, committing itself to the restitution of art stolen by the Nazis or sold under duress, the pact is legally non-binding.

Although Anna was sympathetic to seeing the painting's return, "the matter was not one for her to decide," Epstein says, "because the work was municipal property." In 2010, to fight the Stern estate's claim for Self-Portrait of the Artist, Dusseldorf city council hired lawyer Ludwig von Pufendorf, who had recently become one of Germany's most outspoken critics of art restitution after the Berlin state senate released Berlin Street Scene by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner from Berlin's Bruecke Museum in 2006. The restitution of the painting, which had been the centrepiece of the museum's collection for 26 years, ignited controversy across the European art world.

Anita Halpin, a granddaughter of the Jewish-German art collectors Alfred and TeklaHess, claimed Kirchner's expressionist masterpiece after a lengthy process in which her legal representatives presented evidence that under anti-Semitic persecution, two Gestapo agents forced her grandmother to part with the painting in 1936. Disputing Halpin's claim that Berlin Street Scene was sold under Nazi duress, vonPufendorf, then president of the Bruecke Museum's patrons' association, publicly railed against the decision and called for a parliamentary inquiry into whether the restitution contract was binding.

The uproar escalated and spread when in the fall of 2006, Halpin sold the painting at Christie's New York for $38.1-million (U.S.). Bernd Schultz, then director of the Berlin auction house Villa Grisebach, called the Kirchner return a "betrayal of the German nation." In London, Royal Academy director Sir Norman Rosenthal argued that museums should not be forced to restitute Nazi-looted artwork and that it was a practice that makes the rich richer. Guardian columnist Jonathan Jones wrote that restituting "paintings from the cities where they have the deepest relevance is meaningless and contrary to the public good."

The Dusseldorf Stadtmuseum announced its plans for an exhibition about Max Stern in April, 2014, at a restitution ceremony in the gallery, where it returned to the Stern estate the painting Self-Portrait of the Artist by the 19th-century Romantic artist Wilhelm von Schadow. Five years earlier, in 2009, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project had discovered the work in the inventory of the museum. The painting had been listed as one of the items in the 1937 catalogue for the forced auction at Lempertz.

At the ceremony at the Stadtmuseumwhere the painting was returned to Stern's estate, Susanne Anna announced that under her direction the museum would organize an exhibition to acknowledge the Galerie Stern's importance to the city of Dusseldorf, because the Third Reich had erased its history, as well as the stories of the city's other Jewish art dealers. She explained the show was necessary as a reminder that "art was only one thing stolen by the Nazis. They took everything – rugs, bicycles, cars, carpets, candlesticks and books – turning Germany into a garage sale of Jewish goods to finance the war."

What Anna left out of her speech, however, was the highly arduous process that the Stern heirs had faced in reclaiming Self-Portrait of the Artist, one that took five years in a city known for its conservative values.

"It was complicated," Epstein says, "because Germany has no set laws outlining how to deal with claims." Moreover, the country's civil code states that property cannot be reclaimed more than 30 years after it was lost or stolen. Thus, the door to restituting works through German courts was shut in 1975. While Germany is among 44 countries that voluntarily signed the Washington Principles of 1998, committing itself to the restitution of art stolen by the Nazis or sold under duress, the pact is legally non-binding.

Although Anna was sympathetic to seeing the painting's return, "the matter was not one for her to decide," Epstein says, "because the work was municipal property." In 2010, to fight the Stern estate's claim for Self-Portrait of the Artist, Dusseldorf city council hired lawyer Ludwig von Pufendorf, who had recently become one of Germany's most outspoken critics of art restitution after the Berlin state senate released Berlin Street Scene by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner from Berlin's Bruecke Museum in 2006. The restitution of the painting, which had been the centrepiece of the museum's collection for 26 years, ignited controversy across the European art world.

Anita Halpin, a granddaughter of the Jewish-German art collectors Alfred and TeklaHess, claimed Kirchner's expressionist masterpiece after a lengthy process in which her legal representatives presented evidence that under anti-Semitic persecution, two Gestapo agents forced her grandmother to part with the painting in 1936. Disputing Halpin's claim that Berlin Street Scene was sold under Nazi duress, vonPufendorf, then president of the Bruecke Museum's patrons' association, publicly railed against the decision and called for a parliamentary inquiry into whether the restitution contract was binding.

The uproar escalated and spread when in the fall of 2006, Halpin sold the painting at Christie's New York for $38.1-million (U.S.). Bernd Schultz, then director of the Berlin auction house Villa Grisebach, called the Kirchner return a "betrayal of the German nation." In London, Royal Academy director Sir Norman Rosenthal argued that museums should not be forced to restitute Nazi-looted artwork and that it was a practice that makes the rich richer. Guardian columnist Jonathan Jones wrote that restituting "paintings from the cities where they have the deepest relevance is meaningless and contrary to the public good."

Self-Portrait of the Artist by Wilhelm von Schadow.

MAX AND IRIS STERN FOUNDATION

Self-Portrait of the Artist by Wilhelm von Schadow.

MAX AND IRIS STERN FOUNDATION

In the fall of 2013, however, the conversation about Nazi-era art restitution changed. The German publication Focus broke the story of the greatest art find of the 21st century: More than 1,400 pieces were discovered the previous year in the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, who was a Nazi curator and the appointed dealer for Hitler's planned Fuehrermuseum in Linz, Austria. The collection, estimated to be worth more than €1-billion, was described by The Economist as "reading like the syllabus for a course in the history of art."

In the wake of the Gurlitt announcement came news of how after the war, Hildebrand Gurlitt, along with other former Nazis, was able to re-establish his life very easily in Dusseldorf. Presenting himself as a victim of the Third Reich, Gurlittsuccessfully rehabilitated his name, and in 1948 became director of the Dusseldorf Kunstverein, the city's art association for the Rhineland and Westphalia.

Suddenly the provocative debate that von Pufendorf and others had ignited in response to Berlin Street Scene seemed far less relevant than new questions that the media brought to the surface, including: Where did the paintings in Gurlitt'sapartment come from? And how much other Nazi-looted art remained hidden and unrestituted?

Max Stern in Germany, 1925.

NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA ARCHIVES/FONDS MAX STERN

It was against this backdrop that, after five years of making a claim for Self-Portrait of the Artist, the municipality of Dusseldorf, then under the leadership of Mayor Dirk Elbers, was persuaded to return the von Schadow portrait to the estate of Max Stern.

"The city was on solid ground in its legal claim to keep the work," Epstein says. "However, when we asked its officials what was their justification in holding onto stolen property just because the law entitled them to do so, they were morally persuaded to consider our position as well as the Stadtmuseum'sethical responsibility."

Since the restitution of von Schadow's Self-Portrait of the Artist and the announcement of the Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal show, Thomas Geisel defeated Elbers as Dusseldorf's mayor. This past July, Geisel came under pressure when the Max Stern Art Restitution Project initiated a claim to recover Sicilian Landscape (1861) by Andreas Achenbach, a painting registered as missing with Interpol and listed on the German database lostart.de as one of Stern's stolen works.

The piece was spotted in an Achenbach exhibition that originated in the German city of Baden-Baden in 2016, featuring works belonging to the private collector Wolfgang Peiffer.

Peiffer retained the legal counsel of von Pufendorf, who disputed the Stern estate's claim and told The Art Newspaper, "I can assure you that my client will not allow this painting to continue to be listed on the lostart.de database and will seek recourse in court to uphold his rights if necessary." When the exhibition moved from Baden-Baden to its next venue, the Museum Kunstpalast in Dusseldorf, Sicilian Landscape was not included in the show.

According to Dr. Willi Korte, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project's Bavarian-born, Washington-based chief investigator, von Pufendorf launched a series of complaints against the Stern Restitution Project, directed toward the Canadian embassy in Germany, the Holocaust Claims Processing Office in New York and the city of Dusseldorf.

"The last letter, received on Oct. 8, was heavily critical of the Stern project, our work and our mandate," Korte says. The next day the Stadtmuseum's Susanne Anna received verbal notification from city council that the exhibition was cancelled.

"My personal take is that Pufendorf convinced Geisel that the exhibition was too provocative," Korte says.

Geisel's decision is particularly contentious because in the German city of Bonn, the show Nazi Art Theft and Its Consequences opened on Nov. 3 (a parallel exhibition, Degenerate Art: Confiscated and Sold, also launched at Switzerland's Museum of Fine Arts, Bern), where the public now has the opportunity to view, for the first time, a portion of the highly questionable works that Cornelius Gurlitt inherited from his father.

It was against this backdrop that, after five years of making a claim for Self-Portrait of the Artist, the municipality of Dusseldorf, then under the leadership of Mayor Dirk Elbers, was persuaded to return the von Schadow portrait to the estate of Max Stern.

"The city was on solid ground in its legal claim to keep the work," Epstein says. "However, when we asked its officials what was their justification in holding onto stolen property just because the law entitled them to do so, they were morally persuaded to consider our position as well as the Stadtmuseum'sethical responsibility."

Since the restitution of von Schadow's Self-Portrait of the Artist and the announcement of the Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal show, Thomas Geisel defeated Elbers as Dusseldorf's mayor. This past July, Geisel came under pressure when the Max Stern Art Restitution Project initiated a claim to recover Sicilian Landscape (1861) by Andreas Achenbach, a painting registered as missing with Interpol and listed on the German database lostart.de as one of Stern's stolen works.

The piece was spotted in an Achenbach exhibition that originated in the German city of Baden-Baden in 2016, featuring works belonging to the private collector Wolfgang Peiffer.

Peiffer retained the legal counsel of von Pufendorf, who disputed the Stern estate's claim and told The Art Newspaper, "I can assure you that my client will not allow this painting to continue to be listed on the lostart.de database and will seek recourse in court to uphold his rights if necessary." When the exhibition moved from Baden-Baden to its next venue, the Museum Kunstpalast in Dusseldorf, Sicilian Landscape was not included in the show.

According to Dr. Willi Korte, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project's Bavarian-born, Washington-based chief investigator, von Pufendorf launched a series of complaints against the Stern Restitution Project, directed toward the Canadian embassy in Germany, the Holocaust Claims Processing Office in New York and the city of Dusseldorf.

"The last letter, received on Oct. 8, was heavily critical of the Stern project, our work and our mandate," Korte says. The next day the Stadtmuseum's Susanne Anna received verbal notification from city council that the exhibition was cancelled.

"My personal take is that Pufendorf convinced Geisel that the exhibition was too provocative," Korte says.

Geisel's decision is particularly contentious because in the German city of Bonn, the show Nazi Art Theft and Its Consequences opened on Nov. 3 (a parallel exhibition, Degenerate Art: Confiscated and Sold, also launched at Switzerland's Museum of Fine Arts, Bern), where the public now has the opportunity to view, for the first time, a portion of the highly questionable works that Cornelius Gurlitt inherited from his father.

In this circa 1952 file photo, Max Stern and his wife, Iris, are on a ship looking at an advertisement showing art works that they were pursuing from the Stern collection lost during the Nazi period.

AP PHOTO/CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY, FILE

The purpose of the Bonn exhibition, being held in a federal museum and heavily supported by the federal government, is to tell the story of Nazi victims and how they lost their artwork, as well as the country's pledge to see works in the Gurlitt hoard rightfully returned to their owners. German Culture Minister MonikaGruetters has said the Gurlitt show is an indication of her commitment to "how important research into this bitter chapter of Nazi policy remains."

Yet Gruetters has remained silent on the cancellation of Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal and the events unfolding in Dusseldorf. "This reflects a persistent unease in German political circles over Jewish claims," says Marc Masurovsky, co-founder of the Washington-based Holocaust Art Restitution Project, "and coming to terms with a very intimate aspect of the history of the Third Reich, the material dispossession of the Jews which profited immensely non-Jewish civil society, and the failure of postwar society to come to terms with that sad reality."

The exhibition that was to open in February would have addressed these issues head on by educating Dusseldorf's citizens and the international community about events that transpired in the 1930s and 40s, and the importance of understanding Nazi-era restitution in the 21st century.

"Its cancellation is tragic," Epstein says. "Dusseldorf already once expunged Max Stern from history. It is now happening again, with little resistance from those within Germany who are able to stop it."

The purpose of the Bonn exhibition, being held in a federal museum and heavily supported by the federal government, is to tell the story of Nazi victims and how they lost their artwork, as well as the country's pledge to see works in the Gurlitt hoard rightfully returned to their owners. German Culture Minister MonikaGruetters has said the Gurlitt show is an indication of her commitment to "how important research into this bitter chapter of Nazi policy remains."

Yet Gruetters has remained silent on the cancellation of Max Stern: From Dusseldorf to Montreal and the events unfolding in Dusseldorf. "This reflects a persistent unease in German political circles over Jewish claims," says Marc Masurovsky, co-founder of the Washington-based Holocaust Art Restitution Project, "and coming to terms with a very intimate aspect of the history of the Third Reich, the material dispossession of the Jews which profited immensely non-Jewish civil society, and the failure of postwar society to come to terms with that sad reality."

The exhibition that was to open in February would have addressed these issues head on by educating Dusseldorf's citizens and the international community about events that transpired in the 1930s and 40s, and the importance of understanding Nazi-era restitution in the 21st century.

"Its cancellation is tragic," Epstein says. "Dusseldorf already once expunged Max Stern from history. It is now happening again, with little resistance from those within Germany who are able to stop it."