by Sky Goodden, Blouin Art Info

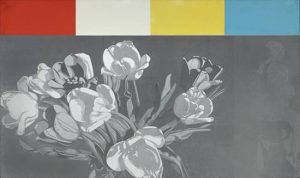

Jack Chambers, “Tulips with Colour Options,” 1966. Courtesy the AGO

In November 2013, an accessible biography and overview of the late painter Jack Chambers — a London, Ontario artist of great significance to the Regionalist movement, whose life was cut short in 1978, and who”s gone underrepresented until recently — emerged through an unlikely portal: online, and for free. The article was written by regarded scholar Mark Cheetham, and published on the new platform The Art Canada Institute. The ACI plans to publish six similar texts this year, eight the next, and then ramp up to an even more prolific pace, where it promises public programming and contemporary analysis, in addition to its coverage on artists ranging from Michael Snow to Emily Carr.

In many regards, the ACI provides an unparalleled resource, not just for scholars and artworld researchers, but for a curious public that feels regularly excluded from the sometimes exculsionary didacticism and impenetrability of our public institutions and journals. Indeed, the ACI publication touts its mission to “[make] Canadian art history a contemporary conversation,” and goes helmed by art historian and critic Sara Angel — equally known for her work in popular publishing (she’s the former editor-in-chief of Chatelaine magazine) as her academic laurels (she was named the Trudeau Doctoral Scholar at the University of Toronto, this year, and spearheaded the ACI with the assistance of Massey Hall master John Fraser). With eminent academic scholars like Martha Langford and François-Marc Gagnon slated to pen forthcoming editions in the book series, Angel’s task lies in maintaining her charge to make the art historical penetrable. BLOUIN ARTINFO Canada caught up with the ACI publisher to query this very aspect, and discuss the holes in Canadian art history, and what sets our canon apart.

How are you making your decisions on which artists get highlighted in this series?

In terms of the selection process, I’m not the person who is doing the deciding. The Institute has Anna Hudson, a curator and professor at York University. She works with a team of advisors, all Canadian art historians. They’re making the selection process. But I can speak a bit to their process: one thing they’re trying to do is provide a balance between well-known artists, like Michael Snow, and artists who should be household names but aren’t yet, like Kathleen Munn, somebody who showed with the Group of Seven in the 1920s and who was very well-regarded at the time; she was the Shary Boyle of her day. But if you haven’t heard of her, the reason is that she fell out of notoriety, and not for any reason except that she was a single woman, and she didn’t have a group of collectors protecting her legacy. One thing we want to do is pay attention to people who have not been recognized, who once were, and put them back into the canon.

Is there an end date that serves as your canon”s ceiling — for instance, would you stop at 1965?

We’re not so much looking at one fixed date, as asking ourselves, “have they made a significant contribution to art history?” In other words, “is he or she a game-changer?” So somebody like Michael Snow, still living, definitely falls into that camp. Another living artist who we intend on covering is Janet Cardiff because of her work with sound installation, and the pivotal change she’s made to our cultural landscape. Another living artist: Jeff Wall. So we’re not so much looking at an artist’s dates, or marking one in history, but more about the artist’s contribution to a cultural dialogue.

In the case of Cardiff, Wall, or Snow, you have people who have been published quite extensively. So you’re not just looking at underdogs. How will these artists be represented in a new way?

Yes, we want to publish on people who have been written about, but in those cases, all the material is new material. So for instance, Michael Snow is being written about by his biographer, Martha Langford, who is currently working on a biography of him. So even though there’s been lots of literature on Snow, Martha feels she’s very much contributing something new with this.

Can you tell me about the “accessible voice” you’re seeking? What are you responding to, when you say that, and what will it look like to have an art history that is more accessible?

A lot of what I’m talking about is trying to avoid what we typically call “art speak.” So often I hear from people who are interested in art, who tell me that they feel like the museum spaces are daunting, or that when they read criticism, they don’t understand what the writer is trying to talk about.

I have a fairly extensive background in both book and magazine publishing — over a decade or so. I built up a large network of editors I’ve become colleagues with. These are people whose expertise is in delivering prose for a broad public audience, not a rarified art audience or an academic one.

Once all of the manuscripts have been written, they go through a lengthy editorial process, a much lengthier process than writers are used to undergoing when they’re writing for an academic or art audience. The editors are constantly asking themselves, “will someone who doesn’t have an art background understand this?”

To antagonize that point, we do adopt a certain vernacular for subjects that are highly specialized, and art history is no exception. So what would we risk losing if this issues too pedestrian a voice?

I don’t think it’s a pedestrian voice — I think honestly it’s just good writing. No one who’s contributing to this project feels like they’re dumbing down their voice.

What we want to do is present complicated and sophisticated ideas in a manner that everyone can be a part of the conversation. I don’t think that involves losing anything.

Why does our Canadian art history have so many holes in it? Why do some of our best artists have so little published on their life and work (ie. Jack Chambers)?

I think there are some definite things we can point to. The first thing: everybody I’ve ever talked to about producing a series of books on Canadian artists, whether print or digital — no one ever says that’s a bad idea. It’s not earthshattering, nor something other people haven’t thought to do. The newness of it resides in the digitization of it, and the bringing together of this broad group of museum professionals and academics. But to create an art book in Canada — say we were going to produce a print book that would retail at Indigo. It’s about a $60-80,000 venture to do. It’s an extraordinarily expensive thing to do. In order to put a price on that book, you’d have to price it at about $25-40. You’d need to print about 20,000 copies of that book. So for years, publishers have thought “wouldn’t it be amazing to do a book on all these people,” but there are simple economics that just don’t work. You can look at the simple fact that Douglas & McIntyre, one of Canada’s most important publishers, has just closed — because even they couldn’t make the economics and math of the book trade work.

So it’s really an issue of dealing with population and numbers. Art books are a huge vehicle in terms of communicating a country’s cultural heritage, but there’s not an expansive art press in Canada. That contributes to it significantly as well. Those two things are pretty enormous in terms of trying to build something. Right now there is an appalling lack of art press in Canada.

On that note, what’s your regard for how contemporary criticism is doing? Is there any difference between our current moment and the art historical dearth you’re addressing?

There’s just not enough of it. The amazing thing is that when I was working on Jack Chambers, I noticed that even just in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, there were so many more art writers in Canada than there are now; and so much of the excellent documentation of Chambers was being done by art journalists. It’s important that we enliven the conversation any way that we can, and one of the things that the ACI wants to do is make a connection between historical artists and contemporary artists, to show that there are important links and ties between the past and present.

How is our art history different from other art histories? Do you see anything defining the Canadian canon?

There’s one hugely important aspect to our art history, our Indigenous art history. One of the things we’re trying to do is redefine what Canadian art history means for a 21st century audience using 21st century technology. Even just a decade ago, Indigenous art history was being studied as a separate topic from colonial art history. Right now, Anna Hudson is saying that on her advisory council, everyone is coming to the table together. That signals a fundamental difference between what’s happening now and what was going on a generation ago. It’s going to produce some very interesting directions for where the Art Canada Institute is headed.

No comments.