William Notman, along with a host of forgotten artists, gets his 21st-century moment

by Ken MacQueen, Maclean’s

The Bounce, Montreal Snowshoe Club, 1886, by Wm. Notman & Son. McCord Museum, Montreal.

William Notman—one of Canada’s pioneering and now near-forgotten artists—sailed from Glasgow to Montreal in 1856, one step ahead of the law. There had been a certain artistic licence in his bookkeeping as he tried to keep the family business afloat; the term “fraud” was levelled by those holding the company’s debts. It was decided that Notman would take one for the clan by shouldering the blame, get a clean start in the new world, and spare prison time for the rest of the family.

It proved an inspired decision, for in Montreal Notman would take what was probably a hobby in the relatively new science of photography, and transform it into a thriving business as one of North America’s pre-eminent photographers. That his work was in demand because his photographs often created a false reality—say, rugged winter outdoor scenes or elaborate costume balls, all created in the magic of his studios—seems entirely appropriate considering his shady past. You might say Notman perfected Photoshop, almost a century and a half before digital manipulation of photos became the norm.

To Sara Angel, founding executive director of the fledgling Art Canada Institute, Notman, the subject of an ebook the institute will publish in April, is the perfect example of a long-neglected artist whose life and work merits resurrection and celebration. “We should be able to make our artists first-class citizens,” says Angel, who is using her position as a Trudeau doctoral scholar in the department of art at the University of Toronto, to do exactly that. The institute, a charity with a mandate to promote art scholarship and history, celebrates its birth at a reception Nov. 28 at U of T’s Massey College. Launching that night will be a vividly rendered ebook about another national treasure, the experimental filmmaker and painter, Jack Chambers. The book, by art historian Mark Cheetham, is the first of 40 free digital volumes on Canadian artists and themes to be published over the next five years.

Books and an institute fill a void that 44-year-old Angel, an arts journalist and former book publisher and magazine editor, discovered early in her second career as an art scholar. “It became apparent to me very quickly that there is a scarcity of material available on Canadian historical artists,” she says. While the Group of Seven or Emily Carr merit academic attention, she says, “anybody who wasn’t a major artist, there really wasn’t that much available—and online there was even less.”

The books—which include one on abstract artist Kathleen Munn, now considered among the most significant artists of the 1920s and ’30s, and one on celebrated multimedia conceptual artist Michael Snow, 83, and still hard at work and travelling the world—will be available in English and French on the institute website or as a free download to mobile devices, tablets and computers. The costs are underwritten by private donations, by expert authors working for modest honorariums, and by museums and artists or their estates who have waived the fees for reprinting their art. They are coffee-table books without the production costs of a physical book, and with more bells and whistles: pop-up glossaries of artistic terms, mini-biographies of fellow contemporary artists, behind-the-scenes looks at the creative process. “We are redefining the conversation of Canadian art history in a 21st-century way, with a 21st-century media tool,” says Angel.

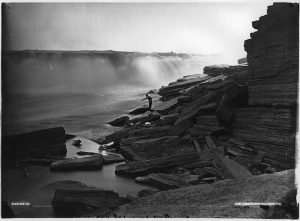

Notman is particularly suited to that mandate. His vision of enhancing reality is as modern as digital manipulation, even if his techniques now seem primitive. Visual arts professor Sarah Parsons’s ebook will offer a delicious exploration of his story, and of studio portraiture and industrial photography of an era when primitive wet-plate photography and excruciating 40-second exposure times were the norm. “Notman had a huge amount of popularity at the turn of the century,” says Angel. “He was known as the photographer to Queen Victoria. He had offices in New York, Boston, across Canada.” At his peak in the 1800s, the Notman name was on 20 studios.

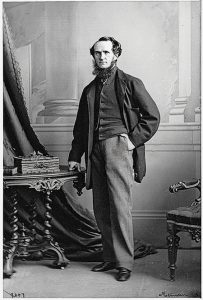

His place in history was impacted by the question that has bedevilled artists through the ages: It’s interesting, but is it art? Few if any museums of his era collected photography, as Parsons notes in her forthcoming ebook. “When Notman’s photographs were reprinted or displayed, it was often for their subjects rather than as examples of their creator’s work.” Perhaps the artistic merit of the overwrought studio photography of the time is debatable, but the historical relevance of his works is beyond question. Those who posed for Notman weren’t just everyday citizens, but also princes and earls, such fathers of Confederation as Sir John A. Macdonald and Thomas D’Arcy McGee, and celebrities ranging from the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Buffalo Bill Cody.

Notman employed an army of retouchers, costumers and artists who created in-studio outdoor scenes with painted canvas backdrops, long before the age of movie sets. Salt and lamb’s wool became snow for scenes of skating or tobogganing; prop trees, bridges, tents and stuffed animals enlivened hunting and camping scenes impossible to recreate in the wild. Notman didn’t invent such tricks, but he elevated them to new levels.

Perhaps the pinnacle of his achievement was his wildly ambitious composite photographs. Group photos at the time were a nightmare; inevitably someone moved and ruined the shot. Yet with skill, cunning and planning, Notman created dynamic photos of skating parties or costume balls featuring dozens, even hundreds of people, with each face sharp and visible. Master drawings were prepared, poses and lighting shadows scripted. Subjects were photographed individually or in small groups in the studio, then cut and pasted to create a master negative. In 1870, one of his first such attempts, a fancy-dress skating carnival at Montreal’s Victoria Rink, involved more than 300 individual portraits, Parsons writes. Of course, 300 faces held the potential for 300 sales. Notman was no fool.

Maclean’s helped save Notman from obscurity. In 1956 the magazine was part of a consortium that purchased his entire archive of almost 500,000 plates, prints and negatives, and donated them to McGill University to be housed in Montreal’s McCord Museum. The magazine then ran a series of Notman photo essays, the first being a sprawling November 1956 cover story written by Pierre Berton. Berton’s story marked the centenary of Notman’s arrival in Canada. “A century has rolled by, and cameras today are as common as fountain pens,” he wrote. Notman was “the Karsh of his era,” Berton said. “Despite the wet plates, the long time exposures and the lack of any artificial light, Notman, always an artist, managed to convey something of the character of his famous subjects.”

“He was Canada’s most famous international artist,” says Angel, “then he went into something of obscurity because his art”— staged studio portraiture—“fell out of style.”

Commercial success is no guarantee of lasting fame. Another case in point, at least until a recent revival, is Jack Chambers. As a brash young traveller in Europe, he arrived unannounced at Picasso’s home, scaled the wall, got an audience with the master and the advice that he should study in Spain, which he did before returning to Canada. In 1970 he stunned the art world by selling Sunday Morning No. 2, an oil-on-wood depiction of his two pyjama-clad sons watching television, for $25,000—the highest price then paid for the work of a living Canadian artist. Yet with his death from leukemia in 1978, at age 47, Chambers began a slow fade in public consciousness.

The institute’s first book brings his work to a potentially vast new audience. To Michael Snow, who knew Chambers, that’s part of the worth of the institute. “If that will attract people to actually see his work, I think it’s very valuable,” Snow says. “He was a very fine artist and shouldn’t just disappear because he’s dead.”

Each book contains a list of locations where an artist’s major works are displayed. The eventual result will be a searchable online directory of where to find the most important works in the country, says Angel, drawing people away from their tablets and into museums. “Once people have a familiarity with art, whether it’s online or in real life, it is the beginning of learning a language,” she says. One that speaks of a wealth of Canadian talent too often lost to the past.

Skating Carnival, Victoria Rink. This composite photo, taken in Montreal in 1870, combines more than 300 individual portraits. McCord Museum, Montreal, gift of Charles Frederick Notman.

William Notman, Photographer, Montreal, 1863. McCord Museum, Montreal.

Chaudiere Falls, Taken in Ottawa in 1870 by William Notman.

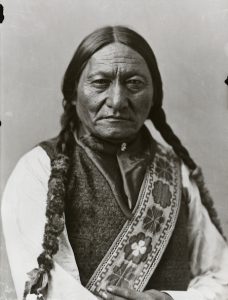

Sitting Bull, taken in 1885 by William Notman.

A portrait of John A. Macdonald, taken in 1863 by William Notman.

No comments.